Examen de las páginas Web sobre aprendizaje de idiomas. Discursos sobre lengua, aprendizaje y aprendices

Examining Language-Learning Websites: Discourses about Language, Learning, and Learners

Avaliação dos sites de aprendizagem de línguas. Discursos sobre língua, aprendizagem e aprendizes

Las páginas web de aprendizaje de idiomas se han convertido en una fuente potencial de aprendizaje de idiomas desde la aparición de la World Wide Web. Al igual que cualquier material pedagógico, estas páginas web promulgan visiones sobre la lengua, el aprendizaje y los estudiantes a través de sus diseños semióticos (contenido y diseño estructural). Este estudio es un intento por explorar estas tres dimensiones mediante el examen de la estructura y los contenidos de Pumarosa, una página web de aprendizaje de inglés, y se centra en los usos de una estudiante-usuaria de este entorno virtual. Este estudio de caso se fundamenta en los elementos de la semiótica multimodal y otras estrategias cualitativas de recolección de datos, tales como entrevistas, grabación de la pantalla de acciones en el entorno virtual, y recuerdo estimulado. Los resultados indican que las visiones sobre la lengua, el aprendizaje y la forma en que los usuarios son posicionados en la página web ejercen una gran influencia sobre los significados que la estudiante-usuaria construye alrededor de esos conceptos

Language learning websites, call, multimodality, social semiotics, discourse (en)

Sites, aprendizagem de línguas, CALL, multimodalidade, semiótica social, discurso (pt)

Álvarez, J.A. (2016a): Language views on social networking sites for language learning: the case of Busuu. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(5), 853-867, DOI: 10.1080/09588221.2015.1069361

Álvarez, J.A. (2016). Framing learners’ identity through semiotic designs on social networking sites for language learning. In Álvarez, J.A., Amanti, C., Keyl, S. & Mackinney, E. (Eds.), Critical views on teaching and learning English around the globe (pp. 17-36). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Baldry, A. & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis. London; Oakville, CT: Equinox Pub. Bax, S. (2003). call—Past, present and future. System, 31(1), 13-28

Betbeder M.L., Tissot R., & Reffay C. (2007). Recherche de patterns dans un corpus d’actions multimodales. EIAH, Lausanne, Suisse, 2007. Retrieved from http:// edutice.archives-ouvertes.fr/edutice-00158881

Brown, J.D. (1995). The elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Bussu language community. Retrieved from Bussu.com

Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1-47.

Candlin, C. (1981). The communicative teaching of English: Principles and exercise typology. London: Longman.

Chapelle, C. (1997). call in the year 2000: Still in search of research paradigms? Language Learning & Technology 1(1), 19-43. Retrieved from: http://llt.msu.edu/vol1num1/chapelle/default.html.

Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second langage acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapelle, C. (2007). Technology and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 98–114.

Clark, C. & Gruba, P. (2010). The use of social networking sites for foreign language learning: An autoethnographic study of Livemocha. In C. H. Steel, M. J. Keppell, P. Gerbic, & S. Housego (Eds.), Curriculum Technology Transformation for an Unknown Future, Proceedings of the 2010 ascilite Conference (pp.164-173). Sydney.

Donaldson R. & Haggstrom, M. (Eds.). (2006). Introduction. In Changing language education through call (pp. VI-XII). Abingdon, England: Routledge.

Dracona, A. & Handa, C. (2000). Xenes glosses: literacy and cultural implications of the web for Greece. In C. Hawisher & S. Selfe, Global literacies and the worldwide web (pp. 52-73). New York, NY: Routledge.

Egbert, J. (2005). Conducting research on call. In J. Egbert & G. Petrie (Eds.), call research perspectives (pp. 3-8). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Egbert, J. & Petrie, G. (Eds.) (2005). call research perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Englishclub.com. Retrieved from englishclub.com

Evans, M. (Ed.) (2009). Foreign-language learning with digital technology. Cornwall, UK: Continuum.

Fotos, S. & Browne, C. (2004). The development of call and current options. In S. Fotos & C. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on call for second language classrooms (pp. 3- 15). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlboum Associates.

Garrett, N. (1998). Where do research and practice meet? Developing a discipline. Recall, 10, 7-12. doi:10.1017/S0958344000004195.

Gass, S. & Mackey, A. (2000). Stimulated recall methodology in second language research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Glesne, C. (2006). Becoming qualitative researchers. An introduction. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. The social interpretation of language and meaning. London, England: Edward Arnold.

Hampel, R. (2003). Theoretical perspectives and new practices in audio-graphic conferencing for language learning. Recall, 15(1), 21–36.

Hampel, R. & Hauck, M. (2004). Towards an effective use of audio conferencing in distance language courses. Language Learning and Technology, 8(1), 66–82.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman.

Harrison, R. (2013). Profiles in social networking sites for language learning: Livemocha revisited. In M.N. Lamy & K. Zourou (Eds.), Social networking for language education (pp. 100-116). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Harrison, R. & Thomas, M. (2009). Identity in online communities: Social networking sites and language learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies & Society, 7(2) 109–124.

Harry, B. & Clingner, J. (2007). Discarding the deficit model. Educational Leadership, 2, 16-21.

Hawisher, G. & Self, C. (1998). Reflections on computers and compositions studies at the century’s end. In I. Snyder (Ed), From page to screen (pp. 3-19). London, England: Routledge.

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. London, England: Routledge.

Hug, K. & Hu, W. (2005). Criteria for effective call research. In J. Egbert & G. Petrie (Eds.), Call research perspectives (pp. 9-24). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jewitt, C. (Ed.) (2009). An introduction to Multimodality. In The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp.14-27). Abingdon, England: Routledge.

Kartal, E. & Uzun, L. (2010). The internet, language learning, and international dialogue: Constructing online foreign language learning websites. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 11(2), 90-107.

Kelly, C. (2000). Guidelines for designing a good website for ESL students. Internet TESL Journal, 6(3). Retrieved from http://iteslj .org/ Articles/Kelly-Guidelines.html.

Kern, R. (2006). Perspectives on technology in learning and teaching languages. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 183-210.

Kern, R., Ware, P., & Warschauer, M. (2004). Crossing frontiers: New directions in online pedagogy and research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 243-260. DOI: 10.1017/S0267190504000091.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality a social semiotic approach to communication. London, England: Routledge Falmer.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. London, England: Arnold.

Lamy, M.N. & Zourou, K. (Eds.) (2013). Social networking for language education. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011a). Key concepts in language learning and language education. In J. Simpson (Ed.), Routledge handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 155-170). London, England: Routledge.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011b). A complexity theory approach to second language development/acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 48-72). London, England: Routledge.

Learn English Online. Retrieved from http://www.learnenglish-online.org/

Lee, J. & Vanpatten, B. (1995). Making communicative language teaching happen. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Lemke, J.L. (1989). Social semiotics: A new model for literacy education. In D. Bloome (Ed.), Classrooms and literacy (pp. 89-109). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Coorporation.

Lemke, J.L. (2006). Toward critical multimedia literacy: Technology, research and politics. In M. McKenna, D. Reinking, L. Labbo, & R. Kieffer (Eds.), International handbook of literacy and technology (pp. 3-14). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Levy, M. (2002). call by design: Discourse, products and processes. Recall, 14(1), 58-84.

Levy, M. & Stockwell, G. (2006). call dimensions. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Liddicoat, A. & Scarino, A. (2013). Understanding language. In Intercultural language teaching and learning (pp. 11-17). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative Language Teaching: An introduction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, M., Evans, M., Horwitz, E., Lee, S., McCrory, M., Park J.B., & Meadows, C. (2013). A study of the use of social network sites for language learning by university ESL students. In M.N. Lamy & K. Zourou (Eds.), Social networking for language education (pp.137-157). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Liu, M., Traphagan, T., Huh, J., Ihn, Y., Choi, G. & McGregor, A. (2008). Designing websites for ESL learners: A Usability testing study. calico Journal, 25(2), 207-240.

Livemocha. Retrieved from http://livemocha.com/

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G. (2011). Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative Research and case study. Applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Moll, L. (1992). Bilingual classroom studies and community analysis: Some recent trends. Educational Researcher, 21(2), 20-24.

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What Is Web 2.0? Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Retrieved from: http://oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=5,

Pumarosa.com. Retrieved from http://www pumarosa.com/.

Reinhardt, J. (2012). Accommodating divergent frameworks in analysis of technology-mediated L2 interaction. In M. Dooly, & R. O’Dowd (Eds.), Researching online interaction and exchange in foreign language education: Methods and issues (pp. 45-77). Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Richards, J. C. (1990). The language teaching matrix. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Savignon, S.J. (1997). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Shield, L. & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2006). Are language learning websites special? Towards a research agenda for discipline-specific usability. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 15(3), 349-369.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Smith, M. & Salem, U. (2000). Web-based ESL courses: A search for industry standards. CALL-EJ Online 2(1). Retrieved from http://callej.org/journal/2-1/msmith-salam.html.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stevenson, M. & Liu, M. (2010). Learning a language with Web 2.0: Exploring the use of social networking features of foreign language learning websites. calico Journal, 27(2), 233-259.

Strauss, A. & Corbin J. (1990). Basis of qualitative research; grounded theory, procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Susser, B. & Robb, T. (2004). Evaluation of ESL/EFL instructional websites. In S. Fotos & C. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on call for second language classrooms (pp. 279- 295). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Thomas, M. (Ed.) (2008). Preface. In The handbook of research on Web 2.0 and second language learning (pp. XI-XIV). New York, NY: Information Science Reference.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

van, Dijk. T. (1997). Racismo y análisis crítico de los medios. Barcelona, España: Paidós.

van, Dijk. T. (1998). Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. London, England: Sage.

van Leeuwen. T. (1996). The representation of social actors. Texts and practices. In C. Coulthart (Ed.), Readings in critical discourse analysis (pp. 33-69). London, England: Routledge.

van Lier, L. (2002). An ecological-semiotic perspective on language and linguistics. In C. Kramsch, (Ed.), Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives. New York, NY: Continuum.

Wakeford, N. (2004). Developing methodological frameworks for studying the World Wide Web. In D. Gauntlett & R. Horsley (Eds.), Web studies (pp.34-48). New York, NY: Edward Arnold.

Warschauer, M. (2004). Technological change and the future of call. In S. Fotos & C. Brown (Eds.), New Perspectives on call for second and foreign language classrooms (pp. 15- 25). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Digital literacy studies: progress and prospects. In M. Baynham & M. Prinsloo (Eds.), The future of literacy studies (pp. 123-140). Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warschauer, M. & Healey, D. (1998). Computers and language learning: An overview. Language teaching, 31, 57-71.

Warschauer, M. & Kern, R. (2000). Introduction. In M. Warschauer, & R. Kern (Eds.), Network-based Language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 1-19). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Warschauer, M., & Grimes, D. (2007). Audience, authorship, and artifact: The emergent semiotics of Web 2.0. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 1-23.

Widdowson, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wigham, C. & Chanier, T. (2013). Les mondes synthétiques: Un terrain pour l’approche Emile dans l’enseignement supérieur? In C. Ollivier, & L. Puren, (Eds.), Mutations technologiques et nouvelles pratiques sociales: Vers l’émergence de «medias d’apprentissage» ? Recherches et Applications, Le Français dans le Monde, 54, 77-93.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zheng, D., Newgarden, K., & Young, M.F. (2012). Multimodal analysis of language learning in World of Warcraft play: Languaging as values-realizing. Recall, 24, 339-360.

Zourou, K. (2012). On the attractiveness of social media for language learning: A look at the state of the art. ALSIC, 15(1). Retrieved from http://alsic.revues.org/2436

Zourou, K. (2013). Research challenges in informal social networked language learning communities. eLearning Papers, 34, 1-11. Retrieved from www.openeducationeuropa.eu/en/elearning_papers.

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Citaciones

1. José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia, Alejandro Fernández Benavides. (2019). Using social networking sites for language learning to develop intercultural competence in language education programs. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 12(1), p.23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2018.1503318.

Métricas PlumX

Visitas

Descargas

Examining Language-Learning Websites: Discourses about Language, Learning, and Learners

Examen de las páginas Web sobre aprendizaje de idiomas. Discursos sobre lengua, aprendizaje y aprendices

Avaliação dos sites de aprendizagem de línguas. Discursos sobre língua, aprendizagem e aprendizes.

José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia1

1 Escuela de Ciencias del Lenguaje. Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. Correo electrónico: jose.aldemar.alvarez@correounivalle.edu.co.

Artículo recibido el 11 de febrero de 2016 y aprobado el 5 de agosto de 2016

Abstract

Language learning websites (LLW) became a potential source of language learning since the emergence of the World Wide Web. Just as any instructional material, LLWS enact views of language, learning, and learners through their semiotic designs (content and structural design). The study is an attempt to explore these three dimensions by examining the structure and contents of Pumarosa, a LLW, and by focusing on the meaning-making process of one female user of this virtual environment. This case study draws on elements of multimodal semiotics and other qualitative techniques of data collection such as interviews, screen recording of actions on the virtual environment, and stimulated recall. Results indicate that the views of language, learning, and the way users are positioned on the LLW exert significant influence on the meanings that the participant makes of these concepts.

Keywords: Language learning websites, CALL, multimodality, social semiotics, discourse.

Resumen

Las páginas web de aprendizaje de idiomas se han convertido en una fuente potencial de aprendizaje de idiomas desde la aparición de la World Wide Web. Al igual que cualquier material pedagógico, estas páginas web promulgan visiones sobre la lengua, el aprendizaje y los estudiantes a través de sus diseños semióticos (contenido y diseño estructural). Este estudio es un intento por explorar estas tres dimensiones mediante el examen de la estructura y los contenidos de Pumarosa, una página web de aprendizaje de inglés, y se centra en los usos de una estudiante-usuaria de este entorno virtual. Este estudio de caso se fundamenta en los elementos de la semiótica multimodal y otras estrategias cualitativas de recolección de datos, tales como entrevistas, grabación de la pantalla de acciones en el entorno virtual, y recuerdo estimulado. Los resultados indican que las visiones sobre la lengua, el aprendizaje y la forma en que los usuarios son posicionados en la página web ejercen una gran influencia sobre los significados que la estudiante-usuaria construye alrededor de esos conceptos.

Palabras clave: Páginas web, aprendizaje de idiomas, CALL, multimodalidad, semiótica social, discurso.

Resumo

Os sites de aprendizagem de línguas são uma fonte potencial de aprendizagem de línguas desde os inicios da World Wide Web. Como todo material pedagógico, esses sites divulgam visões sobre a língua, a aprendizagem e os estudantes através de suas concepções semióticas (conteúdo e concepção estrutural). Esse estudo visa explorar essas três dimensões avaliando a estrutura e conteúdos de Pumarosa, um site de aprendizagem de inglês, e concentra-se na experiência de uma estudante-usuária nesse entorno virtual. Esse estudo de caso baseia-se nos elementos da semiótica multimodal e outras estratégias qualitativas de coleta de dados, como entrevistas, gravação da tela de ações do entorno virtual e evocação estimulada. Os resultados indicam que as visões sobre a língua, a aprendizagem e a maneira na que os usuários são posicionados no site influenciam os significados que a estudante-usuária constrói desses conceitos.

Palavras chave: Sites, aprendizagem de línguas, CALL, multimodalidade, semiótica social, discurso.

Introduction

Technological applications in education have raised different queries regarding teaching methodologies, learning processes, and the roles assigned to educational agents. In particular, second language education has been impacted by the myriad of possible pedagogical applications emerging from the technological era. The field of English language teaching (ELT) has witnessed the development of Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) as a way to account for the different challenges and opportunities created by the interface between technology and language teaching and learning. Recent progress in the area of computer science, such as the advent of web-based communication, has posed new challenges to CALL and has propelled academics to think about and carry out research on computers and language learning in other ways (Bax, 2003; Chapelle, 1997, 2007; Donaldson & Haggstrom, 2006; Egbert & Petrie, 2005; Evans, 2009; Kern, 2006; Kern, Ware & Warschauer, 2004; Levy & Stockwell, 2006; Wharschauer, 2010). According to Kern (2006), it is necessary to enrich the frameworks for CALL research. The author lists three approaches that have been gaining floor in the scene of computer application and language learning, mainly: systemic functional linguistics, ethnographic research methodology, and semiotic theories.

Of the three theoretical and methodological frameworks, semiotic theory remains one of the perspectives that has received less attention, despite its potential to shed light on the different phenomena that bring about the changing communication landscape on the web. Within the different semiotic approaches, multimodal social semiotics or multimodal semiotics (Jewitt, 2009; Kress, 2010; Lemke, 2006) offers a wealth of theoretical principles and procedures in order to better understand the multimodal textuality of web-based communication or Computer Mediated Communication (CMC-Chapelle, 2001, 2007; Egbert & Petrie, 2005; Kern, 2006; Levy & Stockwell, 2006; Warschauer & Kern, 2000). This study intends to contribute to the limited literature that has partnered these two areas (CALL/CMC and multimodality). Thus, this research aims to generate knowledge that aids in understanding how the semiotic design (contents and structure) of a website conveys discourses about language learning and teaching, cultural exchange, and identity construction among others.

On the other hand, this study intends to overcome a traditional criticism of CALL concerning its instrumental and copious focus on the study of cause-effect relationships between human-computer and learning (Bax, 2003; Chapelle, 1997, 2001; Egbert, 2005; Egbert & Petrie, 2005; Fotos & Browne, 2004; Healey, 1998; Huh & Hu, 2005; Kern, 2006; Warschauer, 2004; Warschauer & Garrett, 1998; Warschauer & Kern, 2000). By drawing on a sociocultural approach, the study contributes to the current research approaches that seek "to understand complex relationships among learners, teachers, content, and technology within particular social and cultural contexts" (Kern, 2006, p. 201). In addition, this research provides understanding and raises research participant's consciousness about the agendas and ideologies that underlie websites contents and designs (Wakeford, 2004; Wharschauer, 2010). Likewise, it raises implications for language teachers and educational institutions regarding the selection and use of language learning websites. The study answers the following research questions:

- What discourses about language, learning and learners does the language learning website Pumarosa construct through its semiotic design?

- What are the perceptions of an adult female learner about how the language learning website Pumarosa represents language, learning, and learners?

Language Learning Websites (LLW) in the Field CALL/CMC

A LLW is an online environment characterized by offering language learners practice on some or all of the language skills. Materials consist of grammar explanations, grammar and vocabulary exercises, flashcards, videos, and audio materials. Some of these sites are sometimes organized in the form of an online course with a sequential order of lessons (e.g., pumarosa.com), while some other sites simply offer a wealth of activities and materials without any particular implied sequence of development (e.g., Englishclub.com). From a commercial perspective, these websites are most of the times available for free to any user on the web, although some might have a premium registration to access certain contents. From a technical perspective, there are three kinds of LLWS available on the web. The first group involves sites whose interfaces correspond to Web 1.0 (mostly text centered with little multimedia use); the second one is a hybrid between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. Within this group users can locate sites such as LEO.com, a site that seems to have been adding elements from Web 2.0 to its initial design built on Web 1.0 infrastructure. To the third group belong sites such as Livemocha, Busuu and Rosetta Stone, which make use of the affordances of Web 2.0 platform such as synchronous text and video chat, and social networking.

The affordances of Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 to a great extent have determined scholarship on LLWS, which can be categorized into two moments. The first moment corresponds to the first generation web (Web 1.0) also called the read-only Web that spun around search engines and the connection of information (Thomas, 2008). By contrast, the second moment, marked by the development of the read/write Web or Web 2.0, focuses on connecting people, different forms of user generated content, participation, collaboration, authorship, and interactivity (O'Reilly, 2005; Warschauer & Grimes, 2007). LLWS designed under the technological constraints of Web 1.0, such as the site I will describe in this study, mostly presented content with little opportunities for interaction between the owner of the site and its users, between users and content, and between users themselves. By contrast, through blogs, Wikis, podcasts, video podcasts, and overall social networking, Web 2.0 enabled users to communicate both synchronically and asynchronically. Eventually, social networking gave rise to social networking sites for language learning (SNSLL) (Álvarez, 2015, 2016; Harrison, 2013; Liu et al., 2013) that adopt design elements from traditional social network sites such as Facebook and combine them with features of traditional LLWS, including dialogues, flashcards, and grammar and vocabulary exercises.

Most language learning websites originated during the late 90s when the World Wide Web began operating. Smith and Salam conducted one of the first studies on LLWS in 2000. They examined 35 LLWS on criteria that included: course length, equipment required, type of syllabus, access to a teacher, and cost. In a similar vein, Kelly (2000) proposed a set of guidelines for designing websites for esl students, while Susser and Robb (2004) put forward a framework for the "evaluation of ESL/EFL instructional websites." Kartal and Uzun (2010) carried out a study of 28 online foreign LLWS of different languages and, as a result, the authors advocated for standardization and accreditation of language teaching websites as a way to facilitate website usability and language learning.

Kartal and Uzun touch upon the concept of web usability, an important line of exploration that has developed significantly in the area of e-learning. Shield and Kukulska-Hulme (2006) provide a groundbreaking account of the noteworthy amount of work in the area of second language education from this perspective. Usability, according to them, refers to the "systems [that] are generally regarded as being efficient, easy to learn, effective to use, and enjoyable or engaging from the user's perspective" (p. 349). Levy (2002) addresses usability from the standpoint of design of CALL materials or environments. The author concludes that successful LLWS work as integrated learning environments in which users receive "the information and help they need when they need it" (p. 64). What is important to highlight is that for students, aspects of content organization, clarity of objectives, meaningful feedback, and site navigability are central.

Two of the most recent studies on LLW usability were developed by Liu, Traphagan, Huh, Koh, Choi and McGregor (2008) and Stevenson and Liu (2010). Drawing on similar methodologies, both studies examine well-known LLWS. The first study focused on Stuff for English Learners, English Club, Grammar & Writing, esl Café, Study Zone, while Stevenson and Liu's study assessed Palabea, Livemocha, and Babbel. Despite shedding light on some paramount issues regarding clarity, navigability, and design of the websites, the studies provide little insight on the pedagogical assumptions underlying these environments in regards to language learning, a drawback of many studies of LLWS that has been pointed out by Harrison and Thomas (2009) and Clark and Gruba (2010). Although the two studies were approached from the perspective of usability, the two groups of websites differ in their nature. While the first group represents to a great extent traditional LLWS, the second group (Palabea, Livemocha, and Babbel) belongs to the latest generation of LLWS—SNSLL—, characterized by social networking interfaces. Currently there is a growing body of work on SNSLLS due to their potential to provide multifarious learning and socialization experiences. In the interest of space, I will not review research on SNSLLS since the focus of this article is traditional LLWS. Descriptions of the research conducted on SNSLLS includes the work of Zourou (2012, 2013), Álvarez (2015, 2016) and the edited volume Social networking for language education (Lamy & Zourou, 2013).

Multimodal semiotics and CALL/CMC

The concept of social semiotics emerged from the work of Halliday (1978) and his functional view of language. Halliday claims that texts should be seen as contextually situated signs that embody particular interpretations of experience and forms of social interaction. Hodge and Kress (1980) continuing with his tradition assert that social semiotics inquires into problems of social meaning and describes and explains the "process and structures through which meaning is constituted" (p. 2). This implies that all uses of language are forms of social action (Lemke, 1989). Recently social semiotics has witnessed the move from the dominance of monomodality to multimodality (Kress & Leeuwen, 2001). Newspapers and magazines, computers, and mass media in general have articulated different semiotic modes (e. g., visual, audio, space, written text) that aim to reinforce, make more complex, or produce different meanings. Such an approach requires that researchers adopt a multimodal semiotic approach to semiotic events and semiotic products.

Multimodality refers to approaches that examine communication and representation as phenomena that transcend verbal language. Multimodality focuses on how the variety of communicational forms (modes) people rely on (image, colors, gesture, gaze, body posture) come together to make meaning (Jewitt, 2009; Kress, 2010). This is certainly the case of websites where linguistic texts, videos, images, and audio conflate to make meaning. The view adopted in this study agrees with the general assumptions of multimodal research, mainly that a multimodal ensemble, such as websites, orchestrates meaning-making and enacts certain discourses through the selection, interaction, and configuration of modes (Hawisher & Selfe, 1998; Jewitt, 2009; Kress & Leeuwen, 2001; Wakeford, 2004). The meanings that signs invoke in multimodal texts are shaped by the norms and rules that govern the particular social and cultural context (Jewitt, 2009; Wakeford, 2004).

Of the several theoretical constructs proposed in the field of multimodal social semiotics, this study will mainly address three: discourse, design, and mode. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) discourses "are socially constructed knowledges of (some aspect of) reality" (p. 4). Discourses realize in multiples ways in daily life: they may refer to people, institutions, or situations. They appear in different semiotic modes and use various mediums to articulate meanings and views of reality (e.g., discourse about learning a foreign language). Design is defined by the authors as the motifs behind "choosing modes for representation, and the framing for that representation" (p. 45). It constitutes the blueprint of what would become an entity, an artifact, or an event that will be produced or executed by someone (e.g., the assemblage of visual and language modes in a website to realize discourses about learning). Mode refers to the semiotic resources that materialize any kind(s) of discourse including visual image, language, color, and spatial distribution.

The area of multimodality is fairly recent and its influence in CALL/CMC research is still incipient (Álvarez, 2015). The first studies that combine multimodality with CALL/CMC mostly derive from the implementation of Lyceum, a synchronous audio-graphic (multimodal) environment at the Open University (Hampel, 2003; Hampel & Hauck, 2004). Other research documents how two recent areas of CMC draw on multimodality in the realms of corpus studies and synthetic worlds. A wealth of research on the area of corpus stems from the mulceproject (Multimodal contextualized Learner Corpus Exchange) (Betbeder, Tissot, & Reffay, 2007), while research on synthetic worlds has examined Second Life, following a content and language integrated learning approach (Wigham & Chanier, 2013). Other scholars, including Zheng, Newgarden, and Young (2012) have explored the multimodal affordances of online gaming.

Research Design

This research draws on the principles of qualitative case studies in terms of the size of the sample and the depth of inquiry. Case studies tend to be selective and focus on specific aspects in order to give a full account of the phenomenon under examination (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003). In words of Stake, one of the aims is to make a case of the phenomenon to be studied. In this regard, this study focuses on one website and the relation of meaning construction that it establishes with one female user and that the female user establishes with the virtual environment.

The participant, named Carito, was an adult female of 38 years of age who was living in the United States at the time of the study. Carito came from Colombia, a Latin American country. Before arriving in the us, she felt very little interest in learning English, however, her attitude changed when she knew she was changing countries. This led her to enroll in a two-month English class for beginners before moving to her new residence abroad. Later, in the fall of 2010, she began attending an English class in the us where her teacher recommended her to visit different websites to extend her practice of English. With little experience in online learning and in general the use of the web, she browsed through different English LLWS that her teacher suggested and chose one site called Pumarosa (http://www.pumarosa.com/). Pumarosa has been administered by an American teacher since 2003. The site targets Hispanic learners of English. The general structure and features of Pumarosa fit the first generation of websites (Web 1.0) since it focuses more on developing language skills (vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, etc.) through static contents. The website does not provide any interface for user interaction and user generated content.

The data collection process was conducted during two months in the household environment of the participant in the city of Tucson, us. It consisted of observations of online behavior by means of screen-recording software which the participant agreed to activate once a week at the outset of every study session. Additionally, I conducted two semi-structured interviews and a stimulated record session. The interviews took place during the first and last week of the study, while the stimulated record session was held half way through the research process. I employed a topical or guided interview (Marshall & Rossman, 2011) to explore the experiences, feelings, and opinions about her experience of learning English and the use of the website. Part of the first interview focused on finding out about her experience and views about language learning before arriving in the us and how much access to LLWS she had had before. The second interview explored her experience as a user of the LLW, the reasons for the decisions she made during her work on the virtual interface and more broadly the ways she made sense of what the website offered her as a user. Stimulated recall—an introspective method that prompts the respondent to remember certain event based on a visual, oral, or audio stimulus (Gass & Mackey, 2000)—aimed to elicit information about the actions or behaviors of the participant during the online sessions. Both interviews and the stimulated recall session were audio-recorded.

The data analysis was conducted along with the data collection. Some analytical strategies from multimodality were used to describe the website, mainly, a description of the semiotic design and semiotic modes of the website (Baldry & Thibault, 2006). In this way, to analyze the website pages that the participant visited, a matrix was utilized to map out the modes of communication and their interrelation. The screen-recorded sessions were analyzed by means of another matrix with the purpose of codifying the actions performed by the participant on the website. The data collected from the interviews and stimulated recall session were transcribed and coded in order to find patterns or salient themes and establish discourse categories (Glesne, 2006; Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Findings

This part is divided in two sections. The first one answers the first question regarding the discourses about language, learning, and learners. The second section taps into the second question concerning the perception of the participant in connection to the three dimensions stated in the first question.

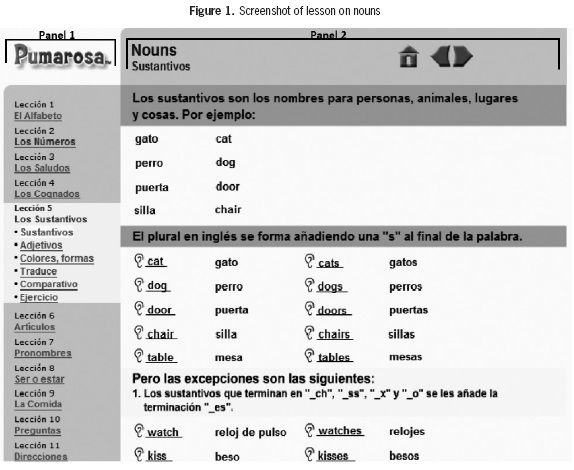

From words to sentences: A structural view of language

One of the greatest breakthroughs of the twentieth century was the development of Structural Linguistics. Structuralism set out as its main purpose to dissect language to its minimum components and establish the relationships between its units. Thus, language was conceived of as a system composed of units such as phonemes and words. Another structural perspective such as Generative Linguistics focused on broader units such as the sentence (Larsen-Freeman, 2011a; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013). Turning to Pumarosa, we can see that its semiotic design is informed by structural views of language that permeate the organization and presentation of instructional materials. Figure 1 presents the screenshot of the lesson on Nouns. From a multimodal perspective, the page draws on several modes of communication including color (e.g., yellow, blue, light green, purple), image (e.g., icons—ear, house, arrows), spatial distribution (two vertical panels with rows) and, especially, the linguistic mode, which carries most of the meaning-making force. As far as layout, the interface is made up of two main panels. The first panel located on the upper left side lists several lessons (lecciones) (El alfabeto, Los números —The alphabet, The numbers) of the Beginner level. The second panel is where the lesson chosen is introduced. Explanations are presented in Spanish and examples in English and Spanish. To introduce the pronunciation of the words, the interface uses an icon of an ear that precedes the written form of the word. The linguistic mode is realized through lists of words and acoustic reproduction. The mode of color is used profusely. For instance, purple is mainly used to signify access to contents. It signals access to a topic through hyperlinks; it highlights grammar rules, and is used for icons that permit navigation to the homepage or to move backward or forward between pages.

The fragmentation of language into smaller parts as well as the use of metalanguage, (nouns, pronouns, articles, cognates etc.) as observed in the left-hand panel on Figure 1, points at the structural view of language that traditionally presented language as static and isolated from the sociocultural dimension that surrounds it use. Grammar lessons on the website adopt typical procedures to present language from structural language teaching methods such as the grammar translation method or Audiolingualism (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). For instance, in the latter method vocabulary and grammar are learned through drilling exercises involving the repetition of words, dialogues, or exercises of sentences in affirmative, negative, and interrogative. In terms of a language syllabus, Pumarosa privileges a structural syllabus as shown above. However, it also adopts features of other types of syllabi such as topical and situational syllabi (Brown, 1995; Richards, 1990), as observed in Lessons 9 and 11 (La Comida and Direcciones — Food and Directions).

A behavioral view of language learning

The motto of the website "observa  (observe, press, listen, speak) (see Figure 2) echoes to some extent the principles of behavioral psychology. First, in the sense that learning is a linear process, and second, it evokes behavioral experiments where subjects or animals were induced to press a button or touch a device as a response to a stimulus. Behavioral psychology reached its highest point of popularity during the 40s and 50s. Second language learning was quite influenced by the work of Skinner, who postulated that language was a behavior and therefore just as all behaviors, it should be learned through absorption from the environment by repetition and imitation (Skinner, 1957). Learning as can be inferred from the motto emerges from observing the words, then listening to them and finally speaking them (repeating them).

(observe, press, listen, speak) (see Figure 2) echoes to some extent the principles of behavioral psychology. First, in the sense that learning is a linear process, and second, it evokes behavioral experiments where subjects or animals were induced to press a button or touch a device as a response to a stimulus. Behavioral psychology reached its highest point of popularity during the 40s and 50s. Second language learning was quite influenced by the work of Skinner, who postulated that language was a behavior and therefore just as all behaviors, it should be learned through absorption from the environment by repetition and imitation (Skinner, 1957). Learning as can be inferred from the motto emerges from observing the words, then listening to them and finally speaking them (repeating them).

All the language units within the website adopt a regular pattern in approaching language topics. The semiotic arrangement of the page for "Nouns" (see Figure 1) presents contents distributed vertically. On the left side, there is a list of topics that learners are supposed to follow based on a hierarchical logic that suggests that languages are learned better if contents are organized from less to more complex items. On the right side of this column, the learner will find the content of the lesson. The lesson comprises a group of rows with lists of words both in English and Spanish. Users are guided to click on each English word so they can listen to the English pronunciation as well as the Spanish translation. Other lessons provide a column with an approximated transcription of the pronunciation of English words (e.g., Welcome> "uelkam"). The linear and hierarchical logic of thinking about language learning contents is not only supported by behavioral views of learning but also cognitivist views of SLA. Such views stand in stark contrast with current sociocultural and ecological views of learning that see language as emergent, non-linear, and dynamic (Larsen-Freeman, 2011b; van Lier, 2002). Concerning the area of CALL, the general structure and exercises of Pumarosa clearly resemble the structural period of CALL, which, as discussed by several scholars (Fotos & Browne, 2004; Kern, 2006; Levy & Stockwell, 2006), was ruled by the tenets of behavioral psychology.

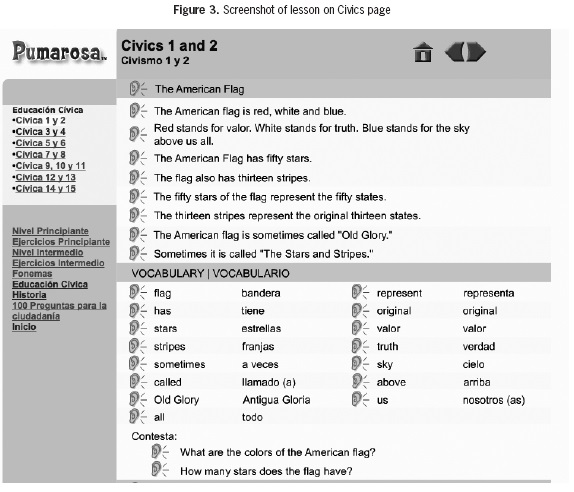

The website was designed for an adult population as presented on the homepage itself: "pumarosa.com is a bilingual, phonetic and interactive esl course for Spanish speaking adults." It is clear that the website tackles a social reality of immigrants in the Unites States and particularly of the South (the owner and website operate from Colorado), where the presence of Spanish speakers is significant and there is a growing need for learning English. However, the website goes beyond teaching English and aims to prepare learners to apply for citizenship in the us, as noted in Figure 2, sections three, four, and five that offer lessons on "Civics," "US History," and "100 questions for citizenship." Although the inclusion of these topics might involve a content-based approach to language learning, a look at how these sections are approached shows that they are still highly ingrained in a structural view of language, focusing on repetition of sentences and vocabulary (see Figure 3).

One examination to the way users (Hispanic speakers) are portrayed through the semiotic design of the website (descriptions and structure of the website) leads to wonder if the website is informed by a discourse reminiscent of the deficit model of education. This model, broadly speaking, focuses on the "disadvantages" and limitations that minority students supposedly bring along to educational processes (Harry & Clingner, 2007; Moll, 1992; Valenzuela, 1999). The view of learners is usually correlated to underachievement and is in many cases unintentionally materialized in the way language is employed to refer to individuals. For example, one of the statements of the homepage states: "'Desarrollé una técnica bilingüe, especialmente diseñada para ayudar a los estudiantes de habla hispana con dificultades para aprender inglés comenta el Prof. Rogers" ("I developed a bilingual technique, especially designed to help Hispanic students with difficulties to learn English" comments 'Prof.' Rogers") (http://www.pumarosa.com/). Here, the designers of the website use three modes of communication to articulate this message. They use written language (including quotation marks), typography (italics), and color (red) to emphasize the message. The inclusion of the word "difficulties" and "help" portray language users of the website as people (Hispanics) in need who require treatment for their difficulties with the language. Further, other statements on the homepage strengthen this discourse: "este sitio fonético y bilingüe está diseñado para ayudarte a aprender inglés tan rápido y fácil como sea possible" (this phonetic and bilingual site is designed to help you learn English as fast and easy as possible"). I reviewed similar online environments to identify if this type of discourse is common across LLWS and found that, generally, particular groups of users are not targeted (e.g., based on nationality or ethnic or language background). Rather than targeting the weaknesses of users, the aims of other websites often foreground that they are designed for cultural enrichment or to meet global and intercultural challenges.

The boundary between good intentions on the part of the designer of the website and the reproduction of a deficit model of education and of learners is very blurry. Compared to other LLWS, Pumarosa adopts a more directive navigational path and normative and hierarchical organization of contents which suggest that adult learners (immigrants) are positioned as lacking technological, linguistic, and social skills not only to use the website but also to become part of the North American ways of life. The website capitalizes on the needs and lacks of many immigrants who face multiple hardships to learn the language and obtain citizenship in the us. But what do learners think about the website? It is relevant to examine how they appropriate or negotiate meanings and identity positions embodied by the website discourses. We turn now to answer the second research question of this study that addresses these queries.

Intuitive agreement and common alignment with the website's discourses

This section analyzes the expressed views and the actions performed by the participant, Carito, on the site. The purpose is to find out her perceptions concerning how the website represented learning and language and how she saw herself represented as a learner on the virtual space. I will tackle these three dimensions in what follows.

The first thing to be taught: "las vocales, el alfabeto, los números, los pronombres, los verbos" ("the vowels, the alphabet, the numbers, the pronouns, the verbs")

One of the issues that struck me as a researcher was the general knowledge that the participant had of metalanguage. As a teacher of adults I have seen that normally people who start English classes do not remember typical linguistic jargon such nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and their function in the structure of the clause. During the second interview I asked the participant where she had learned to speak with such confidence about grammar topics. Carito stated that she did not know exactly, but in part it may have been due to the use of the website or other materials she had been consulting lately.

Although current language teaching approaches deemphasize the traditional dominant role of grammar, instead foregrounding communication and interaction (Canale & Swain, 1980; Candlin, 1981; Harmer, 2007; Lee & Vanpatten, 1995; Littlewood, 1981; Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Savignon, 1997; Widdowson, 1981), Carito's view of language evokes a structural view. It is interesting to notice that the ways she speaks about language resembles to a great extent the view found on Pumarosa. For example, when I asked what she considered a learner of English should be taught, she said: "Fine, well the first thing that one should be taught is vowels, alphabet, numbers, pronouns, verbs..." (Interview 1). This is a list of contents that resembles closely the list of topics found on the website that includes: "alphabet, numbers, greetings...nouns, adjectives, articles, pronouns..." (see Figure 1). The ways she refers to language fits the structural view that is characterized by explicit mentioning of metalanguage in naming the structural components of language. Her view also corresponds to the stance that language is made up of units which when put together would allow to make longer utterances, which is why she starts listing what, for her, would be the smallest units of language: vowels and then the alphabet.

Further support to this discussion is found in Carito's answer about the idea of language that she considered the website emphasized more on: "On a lot of vocabulary, it focuses on vocabulary and then how you would say certain word, adding to it certain content to learn to make longer sentences" (Interview 2). Carito's views and actions on the website match the representation of a vision of language portrayed through the website's semiotic design, a vision that posits language as a system of discrete items (phonemes, words) that need to be strung together into sentences for communication to take place.

How people learn: Carito and the website agree

The findings in regards to the theory of language that underlain the Pumarosa website indicated that a behavioral approach was assumed. The actions and the discourse that accompanies Carito's use of the website represent compelling evidence of her alignment with this view of learning. When I asked Carito about how the website thought people should learn language, she replied: "Listening and looking, listen and look..., at the same time that you are learning the words in English, you are learning the pronunciation" (Interview 2). In general, this description does not distance much from what the site proposes. It actually matches some of the words of the motto of the site: "observe, press, listen, speak." However, more similarities to the discourse of learning enacted by the website are found in the way she speaks about her own idea of learning:

"Researcher: What is your idea of learning a language?

Carito: Listen, practice (repeating) what you listen to, you need to learn vocabulary, begin with small things and then advance little by little, then you can make sentences."

In this sequence it is easy to find the main principles of behaviorism that the website adopts. Thus, what Carito says can be rephrased in this way: learning is fragmented, you need to use parts to put them together in a progressive way; learning happens when there is a stimulus (listening) that will provoke a response (repeating) which in turn will take you to learning (vocabulary and construction of sentences). In conclusion, Carito seems to have been persuaded by the instructional proposal and discourses of the website. Yet, she is still opened to other possibilities as it can be inferred from the phrase: "for now I do" uttered during the second interview:

Researcher: "Do you think the way the website believes people learn corresponds to the way you learn?

Carito: "Yes, for now I do".

Carito's responses were not always consistent. Despite the evidence that the website entirely matched her learning style, in terms of focusing on repetition, guided practice, and little or no possibility to interact with other learners, during the last interview I found out that in fact Carito also enjoyed classes that allowed interactional and communicative practice. She explained, though, that this interactive and communicative approach was followed by her teacher at the school she was attending. One interpretation that arises is that as a language student Carito performs different learner identities drawing on the affordances that the two learning contexts offered her. Although she said she felt a little frightened in a communication-oriented class, she liked it because it challenged her to overcome her shyness. On the contrary, when she was given the option to choose a website, she opted for a virtual space that would allow her to learn at her own pace without need to venture into online interaction with other learners. Perhaps, the answer she provided above: "Yes, for now I do" represents her changing views on language learning. It also represents the two learning spaces she inhabited as she expected to find the most appropriate learning style that would suit the current identity positionings within her new sociocultural milieu in the US.

Learner portrayal: A feeling of deficiency

The first interview with Carito helped me build a general profile of who she was as a language learner. One of the aspects that she described was that her experience with English had been little, a two-month-class before arriving in the us and, generally speaking, she had not done well. According to her, this failure had not been influenced by her lack of interest but her multiple professional and domestic obligations. Additionally, I could find that she had limited experience using the Internet, let alone the use of websites to learn English. During the second interview, I inquire directly about her feelings towards English and its learning to what she asserted that she liked English and wanted to learn it very well.

Carito's perceptions of how learners were represented on the website agreed with Pumarosa's identity construction of the target users: adult Hispanic speakers hurrying to learn the language and in many cases with the aim of applying for citizenship status. She had been following down the line almost everything the website has set up for learners. That is, she followed the order in which the topics were presented and did the exercises as indicated on the website. When I asked her about the possible target population of the website, she replied: "Well, for beginners, for those of us who don't know anything about English, I think." (Interview 2). Later she added:

For Latinos because we speak Spanish, I think for adults because I have seen pages that are different with drawings, animation, very funny and colorful. This is a very serious page; it doesn't have drawings. For me this is OK" (Interview 2).

The voice of the participant evokes the discourse of the website in terms of what is being emphasized: the deficiency of the users. Notice the use of the words "beginners" and then the emphasis put on "those of us who don't know anything." Not only does she seem to be talking about a group but also she is including herself within that group of people who "don't know anything." The use of language uncovers feelings that are loaded with negative connotations. The first sentence of the second quote appears ambiguous. In special, the use of the conjunction "because" implying that some information has been elided. As a whole sentence, this utterance without the ellipsis would read: "the website is created for Latinos because we speak Spanish." This word choice draws attention because it is unclear why the participant used causal language or language reflecting a search for reasons: Is speaking Spanish a problem and thus the website is a solution to it? Further conversations with Carito demonstrated that she was aware of all political, racial, and social tensions that Latinos experience in the us in general, and in particular in the south of the country where a great majority of Latino immigrants concentrates. The possible deficit discourse undergirding subtly the website echoes Carito's own understanding of the still dominant deficit model for the integration of immigrants to life in the us.

Conclusion

The Pumarosa website is an example of a language learning environment that embodies the monolithic principles of the Structural period of CALL in the 70s and 80s (Warshauer & Healey, 1998). It portrays views of language, learning, and users associated with this stage of CALL which adopts structural, and behavioral language views and represents learners as consumers of knowledge with limited agency. Examined from the semiotic point of view, the website embodies the principles of this stage of CALL through its monomodally-oriented layout, centered on the linguistic mode of communication as the primary carrier of meaning. By favoring a structural view of language and a behavioral stance on learning, the website evokes a monolithic view of the world where language learning is monadic, unidirectional, and monological.

Assimilationist models in language education, for instance, sustain a monolithic stance in the sense that they reduce individuals to one perspective, usually the perspective of the dominant culture. In the context of this study, I argue that the deficit model tacitly informing the representation of users of the website adheres to this monolithic perspective. Despite advances in the discipline of CALL and Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) and in particular in the area of LLWS, Pumarosa as well as many other learning environments still preserves a semiotic design akin to Web 1.0 and adheres to monolithic principles of a now considered outdated view of CALL.

CALL has evolved parallel to the development of psychology and linguistics. It has moved from a structural period to a sociocultural and even ecological stage (Álvarez, 2016; Reinhardt, 2012). Current website-learning environments that draw on the affordances of Web 2.0 involve semiotic designs and combination of semiotic modes that acknowledge the social and cultural plurality of users, learning styles, different visions of language and new givens about power (Álvarez, 2015, 2016). In line with Kress (2010) current communicational environments "can be conceptualized as a shift from 'vertical' to 'horizontal' structures of power, from hierarchical to (at least seemingly) more open, participatory relations, captured in many aspects of contemporary communication" (p. 21). Not only do new communicational environments adapt multimodal ways to present contents but also their theoretical principles are founded on a multimodal view of language and learning.

Another conclusion that emerges from this study concerns the role of virtual environments and their semiotic designs in disseminating and reproducing discourses about language, learning, and users. Dracona and Handa (2000) claim that "[u]nderlying grammatical and linguistic structures, as well as graphic design and visual displays, arise directly from specific cultures and bear markers connoting specific classes and ideologies" (p. 65). Van Leeuwen (1996) and van Dijk (1997, 1998) take the same line of argument and allude that representations and discourses of advertisement, tv commercials, and websites have shaping effects on people's cognition. This contention particularly applies to virtual habitats where different modes of communication (written language, speech, color, layout) conjoin to create meanings, as shown above. In turn, this leads me to reflect upon the role of the Pumarosa in infusing ways of thinking about language, learning, and learners on the research participant, Carito.

The analysis of Carito's language learning background, her use of the website, and the different opinions expressed during the interviews and stimulated recall session provide strong evidence that indeed most of her views regarding the three domains mentioned above were shaped through the interaction with the website. As it was shown above the views about language, learning, and learners portrayed on the website manifested in Carito's own understandings and ways of speaking about these dimensions. The fact that Carito was not sure whether her views emerged from the interaction with the website's contents2 demonstrate that discourses are organized and legitimized by political, economic, religious, or educational institutions and are distributed, mostly subconsciously, in mass media, educational systems, and other socialization contexts.

Implications

This study has intended to establish an interdisciplinary dialog between two areas of knowledge that can enrich their frameworks of understanding if they work along. In particular during the last decades scholars (e.g., Kern, 2006; Reinhardt, 2012) in the discipline of CALL have advocated for other forms of examining how learners interact with the new computer mediated communication and in general the new communicational landscapes of the internet. Multimodal social semiotics offers this possibility, thus allowing for a more critical and socio-cultural reading of the phenomenon of language learning on the web. This research is significant because unlike previous work in both areas (CALL and multimodality), it tackled the study of a LLW, integrating some concepts and analytical methodologies of multimodality. Not only did it explore the phenomenon from the perspective of production but also reception in order to account for the ways meaning is made, transmitted, reproduced or contested in LLWS. Studies of this type may contribute to inform and orient language users, teachers, institutions, software designers, and in general policy makers about the possible impact of social, historical, cultural, and ideological structures that underlie and guide meaning-making when interacting with semiotic designs of LLWS.

This experience points at the need to develop more research in the area of CALL and multimodal semiotics in order to better understand not only what could be the best ways to design websites but also what could be the impact of different semiotic designs on language learners. Through the process of carrying out the study I became acquainted with a wide variety of LLWS that make use of different semiotic designs, addressed to different populations. I consider that it is important to offer diverse learning options since learners are not homogenous. I concur with the recommendation of Kartal and Uzun (2010) who warned that a high number of LLWS are not build on the grounds of proper pedagogical criteria. Therefore, research on this area may shed light on the construction of sound criteria that improves online learning environments.

Notes

2 It is relevant to point at that due to the short span of the study, I did not ask the participant direct questions about her views of language or learning during the first interview since I anticipated that it could influence her work on the website and the responses during the second interview. However, during the second interview, I asked her directly how she felt the website had impacted her views about language learning. Carito replied that she had not thought about these issues before.

References

Álvarez, J.A. (2015): Language views on social networking sites for language learning: the case of Busuu. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-17. doi=10.1080/09588221.2015.1069361.

Álvarez, J.A. (2016). Framing learners' identity through semiotic designs on social networking sites for language learning. In Álvarez, J.A., Amanti, C., Keyl, S. & Mackinney, E. (Eds.), Critical views on teaching and learning English around the globe (pp. 17-36). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Baldry, A. & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis. London; Oakville, CT: Equinox Pub.

Bax, S. (2003). CALL-Past, present and future. System, 31(1), 13-28.

Betbeder M.L., Tissot R., & Reffay C. (2007). Recherche de patterns dans un corpus d'actions multimodales. EIAH, Lausanne, Suisse, 2007. Retrieved from http://edutice.archives-ouvertes.fr/edutice-00158881.

Brown, J.D. (1995).The elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Bussu language community. Retrieved from Bussu.com.

Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1-47.

Candlin, C. (1981). The communicative teaching of English: Principles and exercise typology. London: Longman.

Chapelle, C. (1997). CALL in the year 2000: Still in search of research paradigms? Language Learning & Technology 1(1), 19-43. Retrieved from: http://llt.msu.edu/vol1num1/chapelle/default.html.

Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second langage acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapelle, C. (2007). Technology and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 98-114.

Clark, C. & Gruba, P. (2010). The use of social networking sites for foreign language learning: An autoethnographic study of Livemocha. In C. H. Steel, M. J. Keppell, P. Gerbic, & S. Housego (Eds.), Curriculum Technology Transformation for an Unknown Future, Proceedings of the 2010 ASCILITE Conference (pp. 164-173). Sydney.

Donaldson R. & Haggstrom, M. (Eds.). (2006). Introduction. In Changing language education through CALL (pp. VI-XXI). Abingdon: Routledge.

Dracona, A. & Handa, C. (2000). Xenes glosses: literacy and cultural implications of the web for Greece. In C. Hawisher & S. Selfe, Global literacies and the world-wide web (pp. 52-73). New York: Routledge.

Egbert, J. (2005). Conducting research on CALL. In J. Egbert & G. Petrie (Eds.), CALL research perspectives (pp. 3-8). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Egbert, J. & Petrie, G. (Eds.) (2005). CALL research perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Englishclub.com. Retrieved from englishclub.com.

Evans, M. (Ed.) (2009). Foreign-language learning and digital technology. UK: Continuum.

Fotos, S. & Browne, C. (2004). The development of CALL and current options. In S. Fotos & C. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on CALL for second language classrooms (pp. 3- 15). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlboum Associates.

Garrett, N. (1998). Where do research and practice meet? Developing a discipline. ReCALL, 10, 7-12. doi:10.1017/S0958344000004195.

Gass, S. & Mackey, A. (2000). Stimulated recall methodology in second language research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Glesne, C. (2006). Becoming qualitative researchers. An introduction. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hampel, R. (2003). Theoretical perspectives and new practices in audio-graphic conferencing for language learning. ReCALL, 15(1), 21-36.

Hampel, R. & Hauck, M. (2004). Towards an effective use of audio conferencing in distance language courses. Language Learning and Technology, 8(1), 66-82.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman.

Harrison, R. (2013). Profiles in social networking sites for language learning: Livemocha revisited. In M.N. Lamy & K. Zourou (Eds.), Social networking for language education (pp. 100-116). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Harrison, R. & Thomas, M. (2009). Identity in online communities: Social networking sites and language learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies & Society,7(2) 109-124.

Harry, B. & Clingner, J. (2007). Discarding the deficit model. Educational Leadership, 2, 16-21.

Hawisher, G. & Self, C. (1998). Reflections on computers and compositions studies at the century's end. In I. Snyder (Ed), From page to screen (pp. 3-19). London: Routledge.

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. London: Polity.

Hug, K. & Hu, W. (2005). Criteria for effective CALL research. In J. Egbert & G. Petrie (Eds.), Call research perspectives (pp. 9-24). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jewitt, C. (Ed.) (2009). An introduction to Multimodality. In The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 14-27). Abingdon: Routledge.

Kartal, E. & Uzun, L. (2010). The internet, language learning, and international dialogue: Constructing online foreign language learning websites. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education,11(2), 90-107.

Kelly, C. (2000). Guidelines for designing a good website for esl students. Internet tesl Journal, 6(3). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Kelly-Guidelines.html.

Kern, R. (2006). Perspectives on technology in learning and teaching languages. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 183-210.

Kern, R., Ware, P., & Warschauer, M. (2004). Crossing frontiers: New directions in online pedagogy and research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 243-260. doi: 10.1017/S0267190504000091.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality a social semiotic approach to communication. London: Routledge Falmer.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. London: Arnold.

Lamy, M.N. & Zourou, K. (Eds.) (2013). Social networking for language education. London, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011a). Key concepts in language learning and language education. In J. Simpson (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Applied Linguistics (pp. 155-170). London/New York: Routledge.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011b). A complexity theory approach to second language development/acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 48-72). London: Routledge.

Learn English Online. Retrieved from http://www.learn-english-online.org/.

Lee, J. & Vanpatten, B. (1995). Making communicative language teaching happen. USA: Mc-Graw-Hill.

Lemke, J.L. (1989). Social semiotics: A new model for literacy education. In D. Bloome (Ed.), Classroom and literacy (pp. 89-109). USA: Ablex Publishing Coorporation.

Lemke, J.L. (2006). Toward critical multimedia literacy: Technology, research and politics. In M. McKenna, D. Reinking, L. Labbo, & R. Kieffer (Eds.), International handbook of literacy and technology (pp. 3-14). USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Levy, M. (2002). CALL by design: Discourse, products and processes. ReCALL, 14(1), 58-84.

Levy, M. & Stockwell, G. (2006). CALL dimensions. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Liddicoat, A. & Scarino, A. (2013). Understanding language. In Intercultural language teaching and learning (pp. 11-17). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative Language Teaching: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, M., Evans, M., Horwitz, E., Lee, S., McCrory, M., Park J.B., & Meadows, C. (2013). A study of the use of social network sites for language learning by university esl students. In M.N. Lamy & K. Zourou (Eds.), Social networking for language education (pp. 137-157). London, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Liu, M., Traphagan, T., Huh, J., Ihn, Y., Choi, G. & McGregor, A. (2008). Designing websites for esl learners: A Usability testing study. CALICO Journal, 25(2), 207-240.

Livemocha. Retrieved from http://livemocha.com/.

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G. (2011). Designing qualitative research. USA: Sage.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative Research and case study. Applications in education. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Moll, L. (1992). Bilingual classroom studies and community analysis: Some recent trends. Educational Researcher, 21(2), 20-24.

O'Reilly, T. (2005). What Is Web 2.0? Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Retrieved on April 15, 2011, from: http://oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=5,

Pumarosa.com. Retrieved from http://wwwpumarosa.com/.

Reinhardt, J. (2012). Accommodating divergent frameworks in analysis of technology-mediated L2 interaction. In M. Dooly, & R. O'Dowd (Eds.), Researching online interaction and exchange in foreign language education: Methods and issues (pp. 45-77). Bern: Peter Lang.

Richards, J. C. (1990). The language teaching matrix. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Savignon, S.J. (1997). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Shield, L. & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2006). Are language learning websites special? Towards a research agenda for discipline-specific usability. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 15(3), 349-369.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Smith, M. & Salem, U. (2000). Web-based ESL courses: A search for industry standards. CALL-EJ Online 2(1). Retrieved from http://callej.org/journal/2-1/msmith-salam.html.

Stake, R. E. (1995).The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

Stevenson, M. & Liu, M. (2010). Learning a Language with Web 2.0: Exploring the use of social networking features of foreign language learning websites. CALICO Journal, 27(2), 233-259.

Strauss, A. & Corbin J. (1990). Basis of qualitative Research; grounded theory, procedures and techniques. London, UK: Seige Publications.

Susser, B. & Robb, T. (2004). Evaluation of ESL/EFL instructional websites. In S. Fotos & C. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on CALL for second language classrooms(pp. 279- 295). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Thomas, M. (Ed.) (2008). Preface. In The Handbook of Research on Web 2.0 and Second Language Learning (pp. XI-XIV). New York: Information Science Reference.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling. New York: State University of New York Press.

Van, Dijk. T. (1997). Racismo y análisis crítico de los medios.Barcelona: Paidós.

Van, Dijk. T. (1998). Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. London: Sage.

Van Leeuwen. T. (1996). The representation of social actors. Texts and Practices. In C. Coulthart (Ed.), Readings in critical discourse analysis, (pp. 33-69). London: Routledge.

Van Lier, L. (2002). An ecological-semiotic perspective on language and linguistics. In C. Kramsch, (Ed.), Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives. New York: Continuum.

Wakeford, N. (2004). Developing methodological frameworks for studying the World Wide Web. In D. Gauntlett & R. Horsley (Eds.), Web studies (pp. 34-48). USA: Edward Arnold.

Warschauer, M. (2004). Technological change and the future of CALL. In S. Fotos & C. Brown (Eds.), New Perspectives on CALL for second and foreign language classrooms(pp. 15- 25). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Digital literacy studies: progress and prospects. In M. Baynham & M. Prinsloo (Eds.), The future of literacy studies (pp. 123-140). Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warschauer, M. & Healey, D. (1998). Computers and language learning: An overview. Language teaching, 31, 57-71.

Warschauer, M. & Kern, R. (2000). Introduction. In M. Warschauer, & R. Kern (Eds.), Network-based Language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 1-19). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warschauer, M., & Grimes, D. (2007). Audience, authorship, and artifact: The emergent semiotics of Web 2.0. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 1-23.

Widdowson, W. (1981). Communicative Language Teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wigham, C. & Chanier, T. (2013). Les mondes synthétiques : un terrain pour l'approche Emile dans l'enseignement supérieur? In C. Ollivier, & L. Puren, (Eds.), Mutations technologiques et nouvelles pratiques sociales: vers l'émergence de «medias d'apprentissage» ? Recherches et Applications, Le Français dans le Monde, 54, 77-93.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. USA: Sage Publications.

Zheng, D., Newgarden, K., & Young, M.F. (2012). Multimodal analysis of language learning in World of Warcraft play: Languaging as values-realizing. ReCALL, 24, 339-360.

Zourou, K. (2012). On the attractiveness of social media for language learning: A look at the state of the art. ALSIC, 15(1). Retrieved from http://alsic.revues.org/2436.

Zourou, K. (2013). Research challenges in informal social networked language learning communities. eLearning Papers 34, 1-11. Retrieved from http://www.openeducationeuropa.eu/en/elearning_papers.

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2016 Revista Folios

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0.

Todo el trabajo debe ser original e inédito. La presentación de un artículo para publicación implica que el autor ha dado su consentimiento para que el artículo se reproduzca en cualquier momento y en cualquier forma que la revista Folios considere apropiada. Los artículos son responsabilidad exclusiva de los autores y no necesariamente representan la opinión de la revista, ni de su editor. La recepción de un artículo no implicará ningún compromiso de la revista Folios para su publicación. Sin embargo, de ser aceptado los autores cederán sus derechos patrimoniales a la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional para los fines pertinentes de reproducción, edición, distribución, exhibición y comunicación en Colombia y fuera de este país por medios impresos, electrónicos, CD ROM, Internet o cualquier otro medio conocido o por conocer. Los asuntos legales que puedan surgir luego de la publicación de los materiales en la revista son responsabilidad total de los autores. Cualquier artículo de esta revista se puede usar y citar siempre que se haga referencia a él correctamente.