Normalising Conflict and De-Normalising Violence: Challenges and Possibilities of Critical Teaching of the History of the Colombian Armed Conflict

Normalizar el conflicto y des-normalizar la violencia: retos y posibilidades de la enseñanza crítica de la historia del conflicto armado colombiano

Este artículo explora la contribución que puede hacer la enseñanza de la historia a procesos de educación para la paz en la escuela, específicamente en el abordaje de la historia del conflicto armado colombiano. Se analizan las narrativas sobre el conflicto presentes en tres textos escolares de historia de amplia difusión, así como en el informe ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: Memorias de guerra y dignidad del Grupo de Memoria Histórica (gmh, 2013), haciendo énfasis en (1) la estructura narrativa, (2) las explicación de las causas de la violencia y (3) la representación de la experiencia de las víctimas. Estos elementos narrativos se examinan a la luz de cuatro categorías de la indagación crítica (planteamiento de problemas, escepticismo reflexivo, multiperspectividad y pensamiento sistémico), para determinar la medida en que contribuyen a fomentar una comprensión crítica de la violencia política. El artículo concluye con algunas recomendaciones para una enseñanza de la historia que, en el marco de la educación para la paz, promueva en los estudiantes reflexiones favorables a la deslegitimación de la violencia y a la no repetición.

educación para la paz, enseñanza de la historia, conflicto armado, pensamiento crítico, deslegitimación de la violencia, análisis narrativo (es)

Acevedo, A. & Samacá, G. (2012). La política educativa para la enseñanza de la historia de Colombia (1948-1990): de los planes de estudio por asignaturas a la integración de las ciencias sociales. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 62, 221-244.

Andrews, M. (2007). Shaping history: Narratives of political change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ávila, S. (2012). Formación de maestros para el presente: Memoria y enseñanza de la historia reciente. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 62, 165-188.

Bajaj, M. (2008). ‘Critical’ peace education. In M. Bajaj (Ed.), Encyclopedia of peace education (pp. 135-146). Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age.

Barber, B. (2009). Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bar-Tal, D. (2000). Shared beliefs in a society: Social psychological analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Barton, K. & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. New Jersey: Routledge.

Barton, K. & McCully, A. (2005). History, identity, and the school currículum in Northern Ireland: An empirical study of secondary students’ ideas and perspectives. Journal of Currículum Studies, 37(1), 85-116. doi:10.1080/0022027032000266070

Barton, K. & McCully, A. (2007). Teaching controversial issues... where controversial issues really matter. Teaching History 127, 13-19.

Bastida, A. (1994). Educar para la paz a través de la guerra. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 227, 97-100.

Bastida, A.; Lugo, S. & Rocasalbas, M. (2008). El conflicto armado en el aula: dos experiencias. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: Revista De Investigación 7, 141-149.

Bekerman, Z. & Zembylas, M. (2012). Teaching contested narratives: Identity, memory and reconciliation in peace education and beyond. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bermúdez, A. (2012). The discursive negotiation of cultural narratives and social identities in learning history. History Teaching and National Identities. International Review of History Education, 5, 203-219.

Bermúdez, A. (2015). Four tools for critical inquiry in history, social studies, and civic education. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 52, 102-118. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res52.2015.07

Bermúdez, A. (2016). Ten narrative keys to normalize or de-normalize political violence in history textbooks. Internal research report. Unpublished manuscript.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning: Four lectures on mind and culture. London: Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18, 1-21.

Carretero, M. (2011). Constructing patriotism: Teaching history and memories in global worlds. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing.

Carretero, M.; Asensio, M. & Moneo, M. R. (2012). History education and the construction of national identities. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age.

Carretero, M.; Haste, H. & Bermúdez, A. (2016). Civic education. In L. Corno & E. M. Anderman (eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (3rd. ed., pp. 295-308). New York: Routledge.

Clark, P. (2006, otoño). Images of aboriginal people in British Columbia Canadian history textbooks. Canadian Issues, 47-51.

Cole, E. (2007). Reconciliation and history education. In E. Cole (ed.), Teaching the violent past: History education and reconciliation (pp. 1-28). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dickinson, P. Lee & Rogers, P. (Eds.). Learning history. London: Heinemann Educational Publishers.

Epstein, T. (2009). Interpreting national history: Race, identity, and pedagogy in classrooms and communities. New York: Routledge.

Etxeberria, X. (2013). La educación para la paz reconfigurada: la perspectiva de las víctimas [preface by Victoria Camps Cervera]. Madrid: Catarata.

Ferro, M. (1984). The use and abuse of history: Or how the past is taught to children. New York: Routledge.

Galtung, J. (1996). Paz por medios pacíficos: Paz y conflicto, desarrollo y civilización (T. Toda, trans.). Bilbao: Gernika Gogoratuz-Bakeaz.

Galtung, J. (1998). Tras la violencia, 3R: Reconstrucción, reconciliación y resolución. Afrontando los efectos visibles e invisibles de la guerra y la violencia. (T. Toda, trans.). Bilbao: Gernika Gogoratuz-Bakeaz.

Garrett, H. J. (2011). The routing and re-routing of difficult knowledge: Social studies teachers encounter when the levees broke. Theory & Research in Social Education, 39 (3), 320-347.

Grupo de Memoria Histórica. (2013). ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad. Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica.

Gómez, D. (2015). La enseñanza de las ciencias sociales en Colombia: lugar de las disciplinas y disputa por la hegemonía de un saber. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 52, 134.

Haste, H. (1993). Morality, self, and sociohistorical context: The role of lay social theory. En G. Noam & T. Wren (Eds.). The moral self (pp. 175-207). Massachusetts: mit Press Cambridge, ma.

Haste, H. & Abrahams, S. (2008). Morality, culture and the dialogic self: Taking cultural pluralism seriously. Journal of Moral Education, 37(3), 377-394.

Herrera, M. C. & Cristancho, J. G. (2013). En las canteras de Clío y Mnemosine: Apuntes historiográficos sobre el Grupo Memoria Histórica. Historia Crítica, 50, 193-210.

Herrera, M. C. & Rodríguez, S. P. (2012). Historia, memoria y formación: Violencia sociopolítica y conflicto armado. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 62, 12-18.

Hess, D. E. (2009). Controversy in the classroom: The democratic power of discussion. New York: Routledge.

Kitson, A. (2007). History teaching and reconciliation in Northern Ireland. In E. Cole (Ed.), Teaching the violent past. History education and reconciliation (pp. 123). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

León Rodriguez, N. & Pérez Vargas, W. (2011). Sociales para pensar 9. Bogotá: Norma.

Lizarralde, M. (2012). Ambientes educativos y territorios del miedo en medio del conflicto armado: Estudio sobre escuelas del bajo y medio Putumayo. Revista Colombiana de Educación, (62), 21-39.

Maraboli, O. & Wiesner, J. J. (2013). En J. E. Melo Pinzón (ed.), Los caminos del saber. Sociales 9. Bogotá: Santillana.

McCully, A. (2012). History teaching, conflict and the legacy of the past. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 7 (2), 145-159.

Mendoza, C., & Prieto, A. (2012). In C. A. Maldonado & M. C. Ortiz

(eds.). Proyecto de ciencias sociales 9: Libro del estudiante. Bogotá: sm.

Nash, G.; Crabtree, C. & Dunn, R. (1997). History on trial: Culture wars and the teaching of the past. New York: Vintage.

Oglesby, E. (2007). Historical memory and the limits of peace education: Examining Guatemala’s memory of silence and the politics of currículum design. In E. Cole (ed.). Teaching the violent past: History education and reconciliation (pp. 175-202). Maryland: Rowman &Littlefield.

Pagès, J. (2003). Ciudadanía y enseñanza de la historia. Reseñas de Enseñanzade la Historia. Revista de la Apehun, 1, 11-42.

Raviv, A.; Oppenheimer, L. & Bar-Tal, D. (eds.) (1999). How children understand war and peace: A call for international peace education. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Reardon, B. (1988). Comprehensive peace education: Educating for global responsibility. New York: Teachers College Press.

Saldaña, J. (2012). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles: Sage.

Salomon, G. & Nevo, B. (eds.) (2005), Peace education: The concept, principles, and practices around the world. New York: Psychology Press.

Salomon, G. (2004). A narrative-based view of coexistence education. Journal of Social Issues, 60 (2), 273-287. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00118.x

Savenije, G.; Van Boxtel, C. & Grever, M. (2014). Learning about sensitivehistory: “Heritage” of slavery as a resource. Theory & Research inSocial Education, 42 (4), 516-547.

Sears, A. (2011). Historical thinking and citizenship education: It is time to end the war. New Possibilities for the Past: Shaping history education in Canada, 344, 364.

Seixas, P. (Ed.) (2004). Theorizing historical consciousness. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Seixas, P. & Morton, T. (2013). The big six: Historical thinking concepts. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Shaheed, F. (2013). Report of the special rapporteur in the field of cultural rights on the issue of writing and teaching of history, with a particular focus on history textbooks. United Nation General Assembly.

Shemilt, D. (1980). Evaluation study: Schools council history 13-16 project. Edinburgh: Holmes McDougall.

Sheppard, M.; Katz, D. & Grosland, T. (2015). Conceptualizing emotions in social studies education. Theory & Research in Social Education, 43 (2), 147-178.

Symcox, L. & Wilschut, A. (2009). National history standards: The problem of the canon and the future of teaching history. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age.

Tulviste, P. & Werstch, J. V. (1994). Official and unofficial histories: The case of Estonia. Journal of Narrative & Life History, 4, 311-329.

Vélez, G. & Herrera, M. (2014). Formación política en el tiempo presente: Ecologías violentas y pedagogía de la memoria. Nómadas, 41, 148-165.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Wenden, A. L. (2007). Educating for a critically literate civil society: Incorporatingthe linguistic perspective into peace education. Journal of Peace Education, 4 (2), 163-180. doi:10.1080/17400200701523561

Wertsch, J. V. (1997). Narrative tools of history and identity. Culture & Psychology, 3 (1), 5-20.

Wertsch, J. V. (2004). Specific narratives and schematic narrative templates. Theorizing historical consciousness.

Wills, M. E. (2015). Los tres nudos de la guerra colombiana: Un campesinado sin representación política, una polarización social en el marco de una institucionalidad fracturada, y unas articulaciones perversas entre regiones y centro. Comisión Histórica del Conflicto y sus Víctimas. Contribución al entendimiento del conflicto armado en Colombia (pp. 762-809). Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Zembylas, M. (2014). Theorizing “Difficult knowledge” in the aftermath of the “Affective turn”: Implications for currículum and pedagogy in handling traumatic representations. Currículum Inquiry, 44 (3), 390-412.

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Citaciones

1. Tina Magazzini. (2024). United in Diversity? Transnational Heritage in Europe and Southern Africa Between Memory and Anticolonialism. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 45(1), p.93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2023.2290065.

2. Angela Bermudez, Terrie Epstein. (2020). Representations of violent pasts in memorial museums. Ethical reflection and history education (Las representaciones de pasados violentos en museos memoriales. Reflexión ética y enseñanza de la historia). Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 43(3), p.503. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2020.1772541.

3. Serhat Tutkal. (2024). Moral Legitimation and Delegitimation of State Violence in Colombia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-024-09471-8.

4. Michelle J. Bellino, Marcela Ortiz-Guerrero, Julia Paulson, Angie Paola Ariza Porras, Ibeth Danelly Cortes, Sebastian Ritschard, Ariel Sánchez Meertens. (2022). ‘Are we doing Cátedra de Paz?’ Teacher perspectives on enacting peace education in Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Peace Education, 19(3), p.255. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2022.2146076.

5. Angela Bermudez. (2021). Historical Justice and History Education. , p.269. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70412-4_13.

6. Vicky Panossian. (2021). Analyzing diasporic pedagogical representations of historical violence against women: The case of Armenians of the Levant. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 43(2), p.165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2021.1911287.

7. Yeraldine Aldana-Gutiérrez. (2021). Possible Impossibilities of Peace Construction in ELT: Profiling the Field. HOW, 28(1), p.141. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.28.1.585.

Métricas PlumX

Visitas

Descargas

Normalising Conflict and De-Normalising Violence: Challenges and Possibilities of Critical Teaching of the History of the Colombian Armed Conflict

Normalizar el conflicto y des-normalizar la violencia: retos y posibilidades de la enseñanza crítica de la historia del conflicto armado colombiano

Normalizar o conflito e desnormalizar a violência: retos e possibilidades no ensino crítico da história do conflito armado colombiano

Angélica Padilla*

orcid.org/0000-0001-6041-6110

Ángela Bermúdez**

orcid.org/0000-0002-5269-6420

* Máster en Psicología de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia y actualmente doctoranda del Programa: Derechos Humanos, Retos Éticos, Sociales y Políticos de la Universidad de Deusto (Bilbao, España). Con el apoyo de una beca Erasmus Mundus de la Unión Europea, realiza su investigación Formación de Docentes para la Enseñanza de la Historia de la Violencia Política Reciente: Retos y Oportunidades de la Educación para la Paz en la Escuela bajo la dirección de Angela Bermudez. Se desempeña como asistente de investigación en la línea Conflicto y Culturas de Paz del Centro de Ética Aplicada de Deusto. Correo electrónico: angelica.padilla@deusto.es.

** PhD en Educación de la Universidad de Harvard. Coordina la línea de investigación Conflicto y Cultura de Paz del Centro de Ética Aplicada de la Universidad de Deusto (Bilbao, España) Es Investigadora Principal (IP) del estudio internacional Comprensión Crítica de la Violencia Política a través de la Enseñanza de la Historia, financiada por una beca Marie Curie de la Unión Europea (FP7-PEOPLE-2012-CIG) y por una beca de investigación de la Fundación Spencer Realiza investigación cualitativa en temas de educación ciudadana, para la paz y enseñanza de a historia. Correo electrónico: angeber@deusto.es.

Para citar: Padilla, A., &; Bermúdez, A. (2016). To normalize conflict and denormalize violence: challenges and possibilities in a critical teaching of history of the colombian armed conflict. Revista Colombiana de Educación, (71), 187-218.

Recibido: 01/03/16 Evaluado: 07/03/16

Abstract

This article explores the contribution history teaching may make toward peace education processes in school, specifically by addressing the history of the Colombian Armed Conflict. We analyze narratives about the armed conflict which are present in three widely disseminated history school textbooks, as well as the ¡Basta Ya!, Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity report, drafted by the Historical Memory Group (GVH, 2013). Our analysis emphasizes: i) narrative structure, ii) explanation of the causes of violence, and iii) the representation of victims' experience. We examine these narrative elements in light of four critical inquiry categories (Problem Posing, Reflexive Skepticism, Multiperspectivity and Systemic Thinking), in order to establish the extent to which the former help foster a critica understanding of political violence. The article ends with some recommendations for a kind of history teaching capable of nurturing -in the framework of peace education-reflections that favor delegitimization of violence and non-repetition.

Keywords: Peace education, history teaching; armed conflict; critical thinking; delegitimization of violence; narrative analysis.

Resumen

Este artículo explora la contribución que puede hacer la enseñanza de la historia a procesos de educación para la paz en la escuela, específicamente en el abordaje de la historia del conflicto armado colombiano. Se analizan las narrativas sobre el conflicto presentes en tres textos escolares de historia de amplia difusión, así como en el informe ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: Memorias de guerra y dignidad del Grupo de Memoria Histórica (GMH, 2013), haciendo énfasis en (1) la estructura narrativa, (2) las explicación de las causas de la violencia y (3) la representación de la experiencia de las víctimas. Estos elementos narrativos se examinan a la luz de cuatro categorías de la indagación crítica (planteamiento de problemas, escepticismo reflexivo, multiperspectividad y pensamiento sistémico), para determinar la medida en que contribuyen a fomentar una comprensión crítica de la violencia política. El artículo concluye con algunas recomendaciones para una enseñanza de la historia que, en el marco de la educación para la paz, promueva en los estudiantes reflexiones favorables a la deslegitimación de la violencia y a la no repetición.

Palabras clave: Educación para la paz; enseñanza de la historia; conflicto armado; pensamiento crítico; deslegitimación de la violencia; análisis narrativo.

Resumo

Este artigo explora a contribuigao que pode fazer a educagao da história á processos de educagao para a paz na escola, principalmente na abordagem da história do conflito armado colombiano. Analisam-se as narrativas sobre o conflito presentes em tres textos da escola da amplia difusao, assim como no informe ¡Basta Ya! Memorias de guerra y dignidad do Grupo de Memória Histórica (GMH, 2013), fazendo enfase em (1) a estrutura narrativa, (2) a explicagao das causas da violencia y (3) a representagao da experiencia das vitimas. Estes elementos narrativos se examinam á luz de quatro categorias da indagagao crítica (problematizagao, ceticismo reflexivo, multiperspectividade e pensamento sistémico), para determinar a medida na que ajudam á incentivar uma compreensao crítica da violencia política O artigo termina com algumas recomendagóes para um ensino da história que, no marco duma educagao para a paz, promova nos estudantes reflexóes favoráveis á des legitimagao da violencia e á nao repetigao.

Palavras chave: Educagao para a paz; ensino da história; conflito armado; pensamento crítico; des legitimagao da violencia; analise narrativo.

Introduction

Colombian society is currently facing a unique, historie opportunity to help close a five-decade chapter that has left nearly 220,000 deaths and 10% of the population displaced from their territories (Wills, 2015). While writing this article, we are about to complete three years of a complex negotiation process between the Colombian State and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Since October 2012, the negotiations in Havana have focused on the terms that might end the armed conflict, and set the foundations for sustainable peace. This dialogue has included unprecedented participation by other actors of the conflict, such as victims, the military, entrepreneurs and academics. From many people's perspective, the Havana process is much more promising than any of the previous attempts to "negotiate peace"; and the possibility of demobilizing the country's largest and oldest guerrilla is now seen as proximate and plausible. However, we know the most difficult part is just beginning. How are we to project a peaceful future, from the standpoint of a past and a present so marked by violence? The recurrent use of the term post-conflict, in referring to the scenario following the signature of agreements, insinuates the complexity of this challenge. If these come to be signed, part of the armed confrontations should cease1. However, we will still have to live with the conflict, or rather, with multiple conflicts that are rooted in the social structure and culture of Colombian society. The cessation of armed confrontation should not generate the illusion that there is no longer a conflict, nor should it conceal the manifold forms of violence that nourish it and suckle on it in a voracious vicious circle.

The Havana agreements bring to the foreground the type of transformations that are necessary to uproot the armed conflict from social, economic and political structures: agrarian development, political participation, illegal drug policy, reparation for victims. Yet, how shall we uproot it from the country's political culture? The results of the last elections reveal a divided public opinion facing the peace process, which in turn suggests that ample sectors of the population endorse the way of war. While some follow this line because they believe in the legitimacy of violence as a means to "solve the conflict", others do so haunted by fear of the risks of relaxing the "hard hand". After the accord's signature, we shall still be confronted by society that is imbued with deep social conflicts, but has been reluctant to acknowledge the roots of those conflicts and has become used to recur to violence to "solve" them. Consequently, what we ought to uproot from culture is the automatic association between conflict and violence. This is not a sufficient, but indeed a necessary condition for a peace process to be sustainable, as well as for non-violent initiatives of conflict management, which have been germinating for decades in the country, to flourish without having to contend with terror or invisibilization.

Such great challenge is a direct responsibility of all educators, particularly social science teachers. It is in our hands to help the new generations critically understand the country's history, in such a way that the conflict is normalized and violence is de-normalized. This is why we ask ourselves: How should the history of the armed conflict be taught? Which ways of telling this story is more favorable for peace building?

In this article, we contrast two different ways of narrating the history of the Colombian Armed Conflict. On one hand, we analyze the account put forth in three 9th grade history textbooks2 , and on the other, we make a contrast with the narrative presented by the "¡Basta Ya!, Memories of War and Dignity" Report (GMH, 2013).

These materials are certainly very different in nature, so our intention to contrast their narratives deserves an explanation. The school textbooks follow official curricular guidelines by the National Ministry of Education, which require that they foster a wide variety of competencies and cover a large amount of social science topics in national, regional and international contexts. They have been produced and distributed by renowned commercial publishing companies that compete for a niche in the educational materials market, especially in the Colombian context, where the use of textbooks is not mandatory. The ¡Basta Ya! report, in turn, published by the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (National Historical Memory Centre (CNMH)) in 2013, aims at the public dissemination of the research conducted by the Grupo de Memoria Histórica (Historical Memory Group, (GMH)) in the framework of the Law for Victims and Land Restitution (Law # 1448 / 2011). Although this report was not produced as a classroom working material, it was indeed conceived as a resource geared to educate the public opinion with regard to an understanding of the conflict. In its nearly 400 pages, the report is written in a relatively simple language, abundantly illustrated with photographs and graphics, and generously laid-out to facilitate its reading.

It might seem unfair or inadequate to compare the narratives contained in the school textbooks and those generated by an academic research process, considering their necessarily different objectives, authorship, contents, formats and circulation mechanisms. However, these differences are precisely what motivate the exercise we propose in this article. In the current context, with the perspective of elucidating the most appropriate ways of teaching the history of the conflict to promote sustainable peace building, we strive specifically to examine different ways of narrating the history of a violent past. As in other countries, school textbooks in Colombia offer an inevitably constricted and general synthesis of the national history; and they have not been written bearing in mind questions about the conflict, violence and peace. By contrast, the ¡BastaYa! report, notwithstanding all its limitations, represents the effort of a research group to look back on the past and to narrate a violent history, seeking to contribute toward building a peaceful future. Thus, how do narratives change when explicit questions on the conflict, violence and peace are given a leading role? To what extent do these different narratives mark possibilities to develop a critical understanding of violence?

The analysis we present focuses on three aspects: i) the narrative structure, ii) the explanation of the causes of violence, and iii) the representation of the victims' experience. In the discussion of results, we expound how these aspects constitute fundamental elements in the construction of narratives that normalize or de-normalize violence; thus, they are fundamental to develop a critical understanding of the past, which is crucial for the construction of peace cultures (Bermúdez, 2016). The promising situation of the current peace process underlines the urgency of addressing the challenges and possibilities we discuss in this article; still, it is actually the long history of violence, trauma and despair, what makes this discussion so important.

Considering the literature

This study is based on different bodies of literature on history teaching and peace education, and on the growing articulation between these two fields of inquiry (Barton & Levstik, 2004; Bermúdez, 2015; Carretero, Haste, & Bermúdez, 2016; Cole, 2007; Herrera & Rodríguez, 2012; McCully, 2012; Pagés, 2003; Sears, 2011).

Recent production in both fields highlights research on the role narratives play in the understanding of social phenomena. Various researchers have revisited foundational theories by Bruner (1990, 1991) and Vygotsky (1978) on how individuals structure a sense of themselves and of their reality through "narrative thought". On this basis, they have studied processes by which people adopt available narratives from their socio-cultural contexts, as frameworks whence they build their understanding of current or past social issues, and orient their own action in face of such issues (Andrews, 2007; Haste & Abrahams, 2008; Wertsch, 1997). According to Haste (1993), those narratives become social theories that define what is taken for granted and what is contested, what is considered "natural" or "normal", and what is seen as "problematic". Thus, narratives help establish coherence between individual and collective identities and experiences. Research on narrative processes in peace education has focused on explaining how social narratives affect the way in which individuals explain conflict situations, construe representations of "the other", based on which they interpret their actions and justify how they themselves relate to their "opponents" (Bar-Tal, 2000; Bekerman & Zembylas, 2012; Salomon, 2004). Various case studies illustrate these processes and their consequences in profoundly divided or confronted societies, such as Northern Ireland, Israel, Palestine, Croatia, Cyprus or Rwanda (Barber, 2009; Raviv, Oppenheimer, & Bar-Tal, 1999; Salomon & Nevo, 2005).

In the field of history teaching and learning, researchers in different countries have studied the ways school textbooks define "official" and "non-official" versions of the past, making history narratives at school often linked to the construction of dominant collective imaginaries and national discourses, which powers regulating education seek to install unto citizens (Acevedo & Samacá, 2012; Carretero, 2011; Carretero, Asensio & Moneo, 2012; Ferro, 1984; Gómez, 2015; Nash, Crabtree & Dunn, 1997; Symcox & Wilschut, 2009). According to Wertsch (2004), specific stories we find in textbooks reflect common schematic narrative templates, which organize the various stories on the past around dominant topics or concepts, such as the construction of the nation, progress or the conquest of liberty. For example, Tulviste & Wertsch (1994) describe this phenomenon in the case of Estonia, particularly from the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union onward. Other studies show how school narratives deal with existing tensions between dominant and marginal, or majority and minority groups' perspectives, as well as the consequences they cast upon the contexts of conflict and reconciliation (Clark, 2006; Kitson, 2007; Oglesby, 2007).

Although many narrative studies on peace education and history teaching have evolved without much dialogue among themselves, there are some important coincidences. Let us emphasize an acknowledgement of i) the interpretive, plural and controversial character of social and historical narratives; ii) the intimate relation between the use of social narratives and the construction of individual and collective identities; iii) the complex relation between historical narratives, collective memory and the disciplinary historical explanation; and iv) the power relations that configure the production and consumption of narratives.

These coincidences underlie a line of inquiry which has recently become stronger; it explores teaching and learning processes with regard to difficult histories, whether they refer to events that generate strong dispute between opposing versions, or to past episodes that are especially violent and traumatic (Barton & McCully, 2005; Epstein, 2009; Herrera & Rodríguez, 2012; Vélez & Herrera, 2014; Zembylas, 2014). These studies shed light on the challenges arising in face of the ethical, emotional and intellectual complexity of uncomfortable past episodes (Bekerman & Zembylas, 2012; Garrett, 2011; Savenije, Van Boxtel & Grever, 2014; Sheppard, Katz & Grosland, 2015). Such challenges have led some "post-conflict" societies to consider options like "passing the page and looking to the future", or temporarily interrupting history teaching on the conflict, while the suffering and social polarization settle. However, these authors also highlight the opportunities opened up by the reflective exploration of these "difficult histories" for peace-building and reconciliation processes.

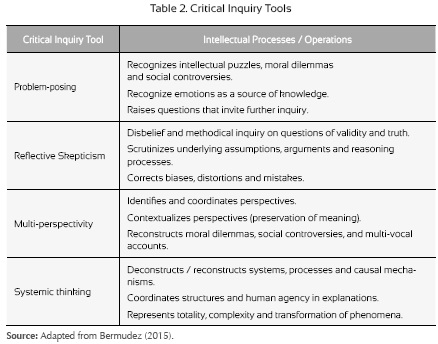

Those opportunities require a way of teaching history that is willing to analyze conflicts in their full complexity, one that is multivocal and open to explore controversial issues reflexively (Barton & McCully, 2007; Galtung, 1996; Hess, 2009; Shaheed, 2013). Various authors agree on the importance to link history teaching and peace education with the development of critical thinking (Bajaj, 2008; Bermúdez, 2012; 2015; Wenden, 2007), thus allowing students to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the causes, dynamics and consequences of social conflicts, to empathically recognize diverse actors' experiences and to build independent positions regarding options for addressing conflicts.

The emphasis on critical thinking is especially notorious in peace education outlooks that address the victims' perspective, the structural roots that cause conflict and violence (including issues of social justice and human rights violations), and the capacity for transformative agency in individuals and communities (Bajaj, 2008; Etxeberria, 2013; Galtung, 1996; Galtung, 1998; Reardon, 1988). These outlooks consider how peace education essentially implies to understand and unlearn the war in contexts permeated by violence, as well as to work on questions like developing interpersonal skills for conflict resolution, the recognition and appreciation of diversity (Bastida, 1994; Bastida, Lugo & Rocasalbas, 2008). Schools must come to terms directly with subjectivities and polarizations configured in war contexts, thus generating a reflection on the imaginaries that are deeply rooted in communities' collective memory and loaded with emotions that are associated to pain and fear (Lizarralde, 2012; Salomon & Nevo, 2005).

The field of history teaching and learning, in turn, is home to various lines of thought in the conceptualization of critical thinking. A rich tradition of inquiry on the development of thought processes intrinsic to the historical discipline understands critical thinking as allowing students to rigorously build and review explanations about issues of the past (Dickinson, Lee, & Rogers, 1984; Shemilt, 1980; Wineburg, 2001). These studies show how boys, girls and youth learn to analyze and interpret documental sources, to reason about the evidence that supports different arguments, to identify and interweave causal relations, to trace processes of change and continuity, or to reconstruct diverse perspectives in their own contexts of meaning. Some researchers contend that critical thinking is the cornerstone that helps interconnect a knowledge of the past with an understanding of relevant current social issues and problems (Barton & Levstik, 2004; Bermúdez, 2015; Seixas, 2004; Seixas & Morton, 2013). From a different yet complementary perspective, other researchers conceive critical history as that which helps students problematize current life conditions on an ethical level, by orienting an exploration of the past in order to understand the configurations of the present, its actors and perspectives on transformation (Ávila, 2012; Gómez, 2015; Herrera & Cristancho, 2013; Herrera & Rodríguez, 2012). These authors also emphasize the role of critical thinking in the clarification of differences and complex relations between official memory, diverse collective memories and academic historical explanations.

Our inquiry integrates these distinct bodies of literature, while analyzing narratives on historical processes that are particularly marked by violence. We do so in attempting to clarify the different mechanisms through which these narratives foster or hinder a critical understanding that might help de-normalize or delegitimize violence, and in this manner, contribute to peace-building (Bermúdez, 2015, 2016).

Methodology

This study is part of an international qualitative research project on the relation between history teaching and the legitimation or delegitimation of political violence. In the first phase, we analyzed narratives about nine historical events that appear in school textbooks and other educational materials from Colombia, Spain and the United States. The Colombian armed conflict was one of three topics analyzed in Colombia. The conceptual and methodological design we use in the article derives from the broader project.

For data collection, three history textbooks-recently published and currently used in classrooms-were selected. All three textbooks follow official curricular guidelines and are intended for ninth grade students, the level which more broadly covers the topic of the Colombian armed conflict. Textbooks sold by renowned publishers were chosen to meet the criterion of wide circulation. Following these criteria, we selected the ninth grade history and social science textbooks by Norma (2011), SM (2012), and Santillana (2013). The chapter corresponding to the period from the mid-twentieth century until present times, where the topic is addressed, were selected from each textbook. While each chapter is approximately 25 pages long, the topic of the Colombian conflict takes more or less one fourth of each chapter.

In order to contrast school textbook narratives, we selected the ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad3 report, drafted by the Grupo de Memoria Histórica (GMH, 2013) and published by the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica4. Following the criteria established in the larger research project, this contrast material should offer an example of an alternative narrative to that presented in school textbooks, which was not determined by official curricular guidelines. Regarding authorship, it should come from academic centers or organizations whose mission included the promotion of historical culture, human rights, and/or peace building. Although such material was not expected to have been designed explicitly for classroom use, it should have a general educational purpose. For analysis of the ¡Basta Ya! report, we selected three chapters that address i) the dimensions and modalities of violence, ii) the origins, dynamics and growth of the armed conflict, and iii) the impacts and damages caused by the latter. Each chapter is approximately 80 pages long, although almost one third of this length is occupied by photographs and graphics. To be sure, the material published by the CNMH is not the only alternative way of narrating the Colombian armed conflict's history, but we chose to focus our analysis on it, given its magnitude and visibility. Among other considerations, we bore in mind that through a formal agreement with the National Ministry of Education, the CNMH has played a fundamental role in designing and implementing educational strategies for the reconstruction of the Colombian Armed Conflict's historical memory and for peace education.

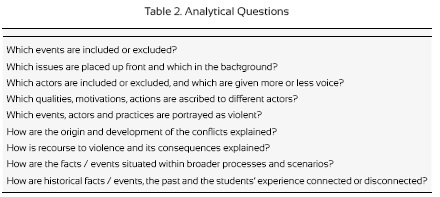

Data analysis employed both inductive and theory-driven coding strategies (Saldaña, 2012). Firstly, we coded all of the materials inductively in order to identify the outstanding topics in the description of events and actors. Additionally, we reviewed the titles and subtitles, running a word frequency count. After this, we followed a set of analytical questions designed to examine the different historical topics in the international project, thus allowing for a comparison between countries, topics or educational resources.

Based on these analyses, we built narrative profiles (Maxwell & Loomis, 2003; Miles & Huberman, 1994), synthesizing how each narrative represents the Colombian Armed Conflict and the violence inherent to it. Finally, we examined the narrative profiles in light of four critical inquiry tools (Bermúdez, 2015), in order to identify the extent to which they allow a problematizing, reflexive, multivocal and systemic understanding of the conflict and of the use of violence.

During the whole process, three researchers read and coded the data separately; afterward they met to compare, discuss and arrive at mutually acceptable coding and narrative reconstructions.

Results

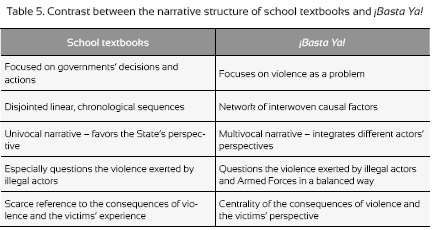

This section shall discuss the results of analysis in three categories: i) structure of the story, ii) explanation of the causes of the conflict and violence, and iii) representation of the victims' experience. Based on an inductive analysis of outstanding topics and a guided exploration through analytical questions, we find that the three textbooks have a common storyline, which is different from that of ¡Basta Ya!. Consequently, as we present the results, we make a contrast between two ways of narrating the history of the Colombian Armed Conflict.

Structure of the narratives

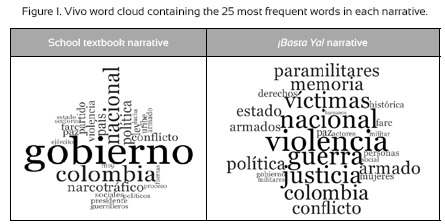

The first difference between the two stories has to do with the narrative structure and the resulting thematic emphasis. By narrative structure, we mean the facts and actors that are included or excluded, the way in which these contents are organized, and the aspects either emphasized or otherwise presented as secondary or marginal. School textbooks have a linear chronological structure, organized along the sequence of presidential periods and government policies and actions. ¡Basta Ya! has an explanatory structure resembling a network, in which different causal factors are interwoven into the process of configuration of the conflict; the diverse manifestations, uses and transformations of violence; its consequences; and the various actors' -particularly the victims'-experience and perspective. The impact of these narrative structures on the thematic emphases is evident because of the frequency of some words vis-à-vis the amount of text in each narrative. According to an NVivo query, the five most frequent words in the textbooks are, in this order: government, national, Colombia, policy and country. In ¡Basta Ya!, the words are violence, war, national, justice and victims.

Narrative structure in school textbooks

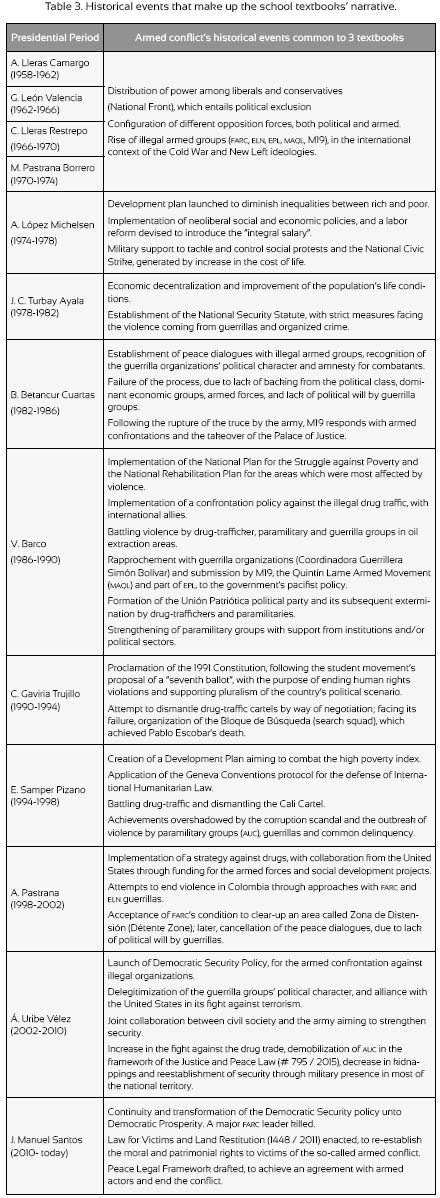

The three chapters selected from the textbooks describe each government's policies and actions in different domains, such as economic development, electoral politics, administrative and institutional management, or social and international policies. The Colombian Armed Conflict is addressed amidst these topics, by referring to the various illegal armed groups' rise and action, as well as the consequent measures taken by the governments in order to restrain or combat them, or seeking to promote peace. The textbooks vary in the level of detail in which they describe actors and events, and in some cases, in the approach with which they touch certain topics. However, there is a body of facts and events in each presidential period, which is common to the three textbooks and serves as a basic structure to portray the armed conflict. In Table 3 we summarize the events included in the three textbooks' central narrative. We have tried to preserve the language used by these materials.

As we analyze this narrative through the lens of our critical inquiry tools, the story's structure stands out, centered on decisions and actions by government leaders, oriented to warrant the population's well-being, security and public order. The narrative's structure is not linked to a problematization of the armed conflict and the use of violence, for the textbooks' fundamental goal is not to generate an explicit reflection on these issues, rather to offer an account of outstanding events in the country's recent history from the State's official perspective. As Table 4 shows, both the conflict and violence appear as recurring phenomena of the national reality. However, the textbooks pose few questions and explanations on the causes and transformations, the different actors' perspectives, the consequences, costs and damages caused, or the various possible interpretations. In a notorious way, these materials treat conflict and violence as the same phenomenon, without explaining in a differentiated way what the conflict is due to, how it is transformed, and why it develops in a violent manner.

In the events and actions included in this story, we have identified two disjointed narrative sequences. On one hand, a sequence alternating the rise and action of different illegal groups with the governments' measures, whether aimed at containment or at fostering negotiated peace. On the other hand, a sequence of social problems (inequality between rich and poor, high poverty index, limited access to resources and opportunities, among others) and the corresponding reforms promoted by governments, aimed to improve the population's life conditions. Hence, events are organized as a simple sequence, breaking up the complex network of causal factors, which would otherwise integrate the two sequences. Further on, we shall see how this is reflected in the causal explanation.

Additionally, a univocal narrative favors a single actor's -the government's- perspective, which is recurrently positioned as a well-intentioned actor, one committed to the Colombian society's security, welfare and peace. When time is due, each government takes necessary measures to restrain the armed groups' attacks, promoting negotiation initiatives, which invariably fail for reasons beyond its control. Other actors (for instance, guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug-traffickers) only appear in the story insofar as they bear a relation with the sequence of actions and governments' reactions. The narrative highlights the formers' actions against the State and society, as well as their lack of will to enact the peace agreements sponsored by the governments. Thus, the actors' representation is markedly dichotomous.

The events selected and the language used (terrorist acts, kidnapping or assassination) make this narrative view violence as mainly derived from illegal groups' actions. In very few cases is the State's participation in human rights violations exposed; although these are explicitly mentioned, this is done with certain ambiguity, which blurs the possibility to critically reflect on the difference between the State's legitimate use and monopoly of force, and the excessive and illegitimate violence as a political tool mobilized by different social actors' clashing interests. The following quote illustrates such ambiguity:

[Alvaro Uribe government's] Democratic Security Policy generated positive results from 2003 onward: the fight against the drug traffic increased, the AUC'S demobilization was achieved in 2005, the kidnappings decreased and a military presence was ensured in most of the territory [...]. On the other hand, as good results were attained in terms of security, there was an increase in forced displacement and in reports of human rights violations. In 2008, the disclosure of the "false positives" cast serious doubts on the democratic security's efficacy; as various investigations revealed, many casualties, presented as guerrillas killed in combat, were really civilians assassinated by some members of the Army (Santillana, 2013, p. 279).

Finally, we observe the structure centered on the governments' actions restricts the visibilization of the consequences of violence, particularly the victims' experience and suffering. At several points, the textbooks suggest that illegal groups' actions generate an institutional crisis, a stagnation of productivity and economic activities, the population's displacement and poverty. Yet these references appear in disperse and laconic phrases, making an understanding of the damage caused and its magnitude more difficult. As we shall explain in detail further down, the absence of the victims' experience and perspective is particularly notorious.

Narrative structure in the ¡Basta Ya! report

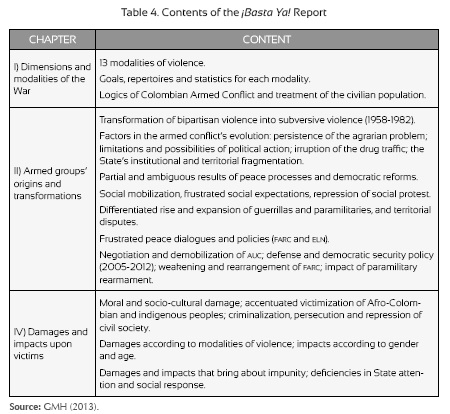

In contrast with the school textbooks, the ¡Basta Ya! narrative is structured by the explanation of the rise and use of violence by different actors in the context of diverse social conflicts, while highlighting the victims' human experience. The report itself asserts, "The GMH established a point of departure for the armed conflict's narrative, in the clarification of the dimension of what happened, when and where it came about, how it occurred, who perpetrated it and who suffered it" (GMH, 2013, p. 31). Thus, the narrative posits a broad perspective for the various modalities of violence, in terms of its actors, explaining its origins and transformations in time, and reconstructing the impacts, damages and memories for those who endured them. The Report consists of five chapters, of which three were analyzed. In Table 4 we synthesize the contents that vertebrate this story's structure:

¡Basta Ya! places the phenomenon of violence in Colombia's recent history, and addresses it as a problem to be interrogated, explained and understood, so as to prevent its repetition. This entails a very different use of the problem-posing tool, inasmuch as it deems the barbarianism and degradation of violence as an object of reflection, thus generating questions and explanations that contest its normalization and legitimation. As shown in Table 4, the report does so by explaining the rise of this problem in conflictive social conditions and particular circumstances, thus demonstrating that violence is not a natural and inevitable phenomenon of human relations, rather a social and historical construction, intimately linked to social dynamics, particular interests and strategies of distinct social groups. Likewise, this effect is attained by underscoring the civilian population's instrumentalization and the impact upon victims and society as a whole, and by setting forth the benefits and costs associated to violence, as well as their unequal distribution.

The report's structure itself suggests a systemic approach that delves deep into the multiple causes, manifestations and consequences of the war. The ¡Basta Ya! narrative interweaves the rise and use of violence by diverse actors in the context of multiple social conflicts that cut across Colombian of political pluralism and possibilities for social movements, the State's institutional and territorial fragmentation, and the penetration of the drug traffic in different social, political and economic spheres.

On a different line, ¡Basta Ya! presents a narrative with various voices, describing different actors' perspective in their understanding of the conflict, territories and civilian population, as well as the interests at stake when they make use of violence. These multiple perspectives contrast, in turn, with the victims' experience; this helps the understanding of their meanings, in light of the consequences for specific populations and society as a whole.

The differential analysis of the modalities of violence employed across the conflict's length and breadth recognizes the violence exerted by the guerrillas and paramilitaries, as well as by the Armed Forces, insofar as they violate human rights and contribute to its exacerbation. "The violence by Public Force members focused on arbitrary detention, torture, selective assassination and forced disappearance, as well as collateral damages produced by bombardments and an excessive and disproportionate use of force" (GMH, 2013, p. 35). The State forces' struggle to recover the monopoly of force in the regions is analyzed, yet without overlooking the way these override the legal framework and democratic principles, or the conditions and factors that make this possible. On the other hand, the narrative recognizes violence in its direct forms (modalities of violence in the armed conflict), as well as structural violence in the different forms of inequality and social exclusion that interact with direct violence.

This narrative places notorious emphasis on the consequences of violence and the victims' experience. It describes the effects of violence in different economic and political levels, while it also documents its impacts on the victims (emotional footprint, moral and socio-cultural damages) with special attention. Considering the victims' gender and age, this analysis differentiates the effects generated by each modality of violence. The emphasis on consequences and damages invites a reflection on the possibilities and need to achieve the different actors' goals through other, non-violent mechanisms.

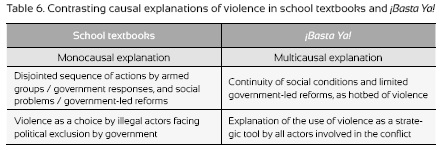

Explanation of the causes of the conflict and violence presented in school textbooks

The systemic thinking tool underlines the fact that critical understanding of social phenomena rests partly on the multicausal explanation of their origins and transformations, shedding light on the social systems and the historical processes embedding particular events. On the other hand, systemic explanations assume an articulation of the individual and collective actors' actions and intentions, with the web of causal factors that interact as driving forces of change and continuity in social historical phenomena.

In contrast with this criterion, school textbooks offer a monocausal explanation of the guerrilla groups' origin. This explanation goes back to the problem of political exclusion during the National Front, which generated different forms of opposition, among which the armed struggle arose. "Such pact [the National Front] brought the violence between parties to an end, but gave rise to the exclusion of other political tendencies; this generated a new stage of violence, during which guerrilla groups emerged" (Santillana, 2012, p. 256). In this way, the configuration of guerrillas is explained as these groups' choice of the violent path, as a revolutionary strategy to promote the uprising of the masses and the overthrow of the excluding regime, instead of opting for other democratic possibilities.

The opposition to the National Front can be divided in three groups: dissident sectors from traditional political parties, the Alianza Nacional Popular (Anapo), and leftist parties. The latter group, in turn, was divided in two sectors: one devoted to the armed struggle and the other to political struggle (Santillana, 2012, p. 260).

The textbooks say little or nothing about the agrarian problem, which sets the foundation for the deeper conflict and influences the political options by guerrilla groups and other social movements.

Thereafter, violence appears intermittently, as the narrative tells about the emergence of new actors, the intensificaron of armed actions by different illegal groups, their confrontations with the State or with each other, and the consecutive governments' responses seeking the defense and control of public order. In this manner, the armed conflict's evolution is explained through a sequence of events and actions, between which a simple relation of action and reaction has primacy. This linear explanation does not help understand the circumstances whence diverse factors hatched and generated the underlying experiences, needs, interests and logics to the different actors' practices and the complex relations between them. For instance, regarding the rise and action of guerrilla groups, one textbook states:

During the National Front, influenced by the Cuban Revolution, many leftists considered there existed conditions for a revolution in the country. Consequently, they encouraged the formation of guerrilla groups in rural zones, like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Popular Liberation Army (EPL). (Santillana, 2012, p. 260).

The guerrilla groups, including leftist guerrillas like the ELN and the FARC, fund themselves through criminal activities such as kidnapping, extortion and the production and trade of narcotics. They struggle to hold control over their areas of influence and strategic corridors (Santillana, 2012, p. 215).

Although school textbooks mention different systemic aspects, such as poverty and social inequality, these are not linked to a causal explanation that might allow for an understanding of the conflict's structural bases and how these contribute to generate violence. "On an economic level, through the National Rehabilitation Plan (PNR), Barco attempted to diminish poverty in those regions most harshly stricken by violence. Additionally, he promoted the State's stronger presence in marginalized areas with a critical public order situation" (Santillana, 2013, p. 265). In this example, let us notice how the textbook describes social reforms and programs as measures aiming to face or alleviate poverty generated by violence, rather than understanding poverty as the material base that generates violence. Although subsequent governments implemented social reform plans with similar goals, their scope and efficacy is not analyzed. In this way, the sequence of actions and reactions hinders an understanding of continuity and transformation in the conflicts' structural bases.

Regarding the upsurge of paramilitary groups in the 80's, one of the textbooks simply states that these rise as a response to the guerrillas' actions. Thereafter, it continues to narrate those groups' consolidation and actions:

In 1997, the paramilitary groups were unified and called Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, under the direction of Carlos Castaño and Salvatore Mancuso. This group disputed the guerrillas' strategic areas, determined to gain the control of drug traffic routes and great natural resources. (SM, 2012, p. 222).

Later, after the paramilitaries' demobilization, criminal bands resurge; these are described as isolated groups, the remainder of paramilitarism: "Between 2003 and 2006, the AUC were demobilized in several of the country's regions. However, some smaller groups continued their criminal activities and passed on to be called Emergent Criminal Bands or Bacrim" (SM, 2012, p. 222).

At this point, it is interesting to notice an important difference between the abovementioned textbook and the other two, insofar as the latter mention different moments whence those armed groups were formed or strengthened, under legal protection. For example, one of the textbooks indicates the following:

During the 90's, paramilitary groups underwent considerable growth, often sponsored by landowners and even some politicians and official force members. Toward the end of the Gaviria government, paramilitarism acquired institutional support with the promulgation of Decree 356 / 1994, which created the Private Security and Vigilance Cooperatives (Convivir); these were underwritten by the Governor of Antioquia at the time, Alvaro Uribe Vélez (Santillana, 2013, p. 276).

Likewise, the textbooks also refer to cases when different State forces backed the paramilitaries, breaking the legal frameworks

The same year when Uribe began his second rule, the "para-política" broke out as his government's first great scandal, in which a good number of senators who were close allies to his political project [...] were accused of holding relationships with paramilitary chiefs (Santillana, 2013, p. 279).

This is doubtless an important explicit mention of the State's responsibility in the paramilitaries' action and strengthening; however, with a scanty reference to such a complex phenomenon, it is difficult to understand its causes and implications for the development of the conflict and the country's political life.

Explanation of the causes of the conflict and violence presented in ¡Basta Ya!

In ¡Basta Ya!, we find a multicausal explanation of violence, which is moreover, situated in mid-term historical processes. The report describes the Colombian Armed Conflict as a heterogeneous process in terms of time and territory, due to the persistence of the agrarian problem, the limitations and possibilities of political participation, the influences and pressures from the international context, the irruption and propagation of drug traffic, the State's institutional and territorial fragmentation, and its reforms' limited scope.

The narrative in ¡Basta Ya! makes explicit explanatory connections bet-ween social problems, the conflict's transformation and the occurrence of violence. On one hand, the explanation includes a broad description of the social conditions that fostered violent opposition strategies:

The agrarian crisis of the time [1960] , as in current times, was evidenced by the extreme inequality in land distribution and the rural population's severe poverty. [...] the narrow scope of social and economic reforms, added to the scenario of military repression and political restriction during the National Front, served as the hotbed of the armed way and the radicalization of some leftist political sectors (GMH, 2013, p. 120).

The "hotbed" or "breeding ground" metaphor serves to explain how scenarios favorable to the armed struggle are generated. On the other hand, the report explains how the structural framework facilitates the premeditated use of violence as a strategic tool, through which different armed groups promote their social, political and economic interests.

It ought to be recognized that the violence endured by Colombia during many decades is not simply a sum of facts, victims or armed actors. Violence is the product of intentional actions, mostly inscribed in political and military strategies, and resting on complex alliances and social dynamics. This way of understanding the conflict allows an identification of different political and social responsibilities in face of what happened (GMH, 2013, p. 31).

The violence presented in ¡BastaYa! is deliberate and planned, insofar as it is an instrument in the dispute over strategic territories needed by the drug traffic, the struggle for access to natural resources and sources of wealth, or the reconfiguration of land property. The different modalities of violence by each group are directly related to these instrumental objectives. The differential analysis of the various modalities of violence, albeit crude, helps visibilize its character as a strategic tool.

All of them have deployed diverse modalities, committing war crimes and crimes against humanity, making the civilian population the conflict's main victim [...]. In terms of violence repertoires, paramilitaries mostly executed massacres, selective assassinations and forced disappearances; they made atrocity a recurrent practice with the purpose to increase their intimidating potential. The guerrillas, in turn, have mainly recurred to kidnappings, selective assassinations and terrorist attacks, as well as forced recruitment and attacks against civilian property. Regarding illegal violence by Public Force members, testimonies and judicial sentences have allowed to establish the employment of modalities such as arbitrary detentions, tortures, selective assassinations and forced disappearances (GMH, 2013, p. 20).

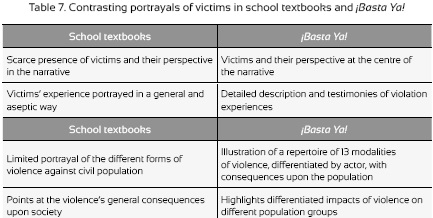

Portrayal of victims in school textbooks

The critical explanation of conflicts and violence rests also on an understanding of the perspectives held by different actors involved. This entails not only identifying relevant actors and their positions, but mostly, reconstructing their perspectives in the social and historical contexts where they have a meaning. In face of situations of conflict and infringement, it is particularly important to understand the actors' experience, including their dilemmas and controversies, or what they win and lose in conflicts. Along this line, the approaches integrated by history teaching and peace education spotlight the urgency of giving the conflicts' victims and their experience of violation a voice.

Considering this criterion, it is inevitable to notice the scarce presence given to victims of violence in school textbooks narratives about the armed conflict. The portrayal of their experience is excessively general and aseptic; they are never given voice to account, through their testimonies, for the emotional, physical, social, cultural and economic damage inflicted upon the civilian population. In these textbooks, there is a diffident description of the violence, the magnitude of the damages, and the detail of the actions perpetrated by different actors. The question is not that the impacts of violence upon the civilian population not be mentioned; the three textbooks do so, moreover, using a language that points at the cruelty and the destruction generated. For example, in the textbooks we find descriptions like the following:

[After describing the violent actions exerted by different armed actors] , most severely harmed by their actions is the civil society. Right and left wing armed groups carry out illegal activities, such as extortion and kidnapping, in order to finance themselves and control crime activities in cities. The conflict's effects are numerous and incalculable, not only in material terms, but also and most gravely, in terms of the destruction of the social tissue in entire regions (SM, 2012, p. 222).

The war against drugs [Plan Colombia] has generated forced and massive displacement of peasants and indigenous people toward the country's main cities. Threatened by guerrillas and paramilitaries, their homes and lands are plundered; they are left with no option but to migrate to other places, where they generally have to start a new life. Due to the presence of AUC in the armed conflict, violence was exacerbated; the methods used by these groups reached unthinkable extremes in the violation of human rights (Norma, 2011, pp. 192,193).

What these fragments show is that even though the textbooks mention phenomena of victimization, like the violation of human rights, displacement, extortion and kidnapping, the description is so general that it cannot take the reader to fathom the costs derived from the use of violence as a political and military strategy for the domination of a territory. These scant mentions do not generate a deeper understanding of which rights were violated, in what ways, or the mark imprinted in society and collective imaginaries. Expressions like "numerous and incalculable effects" or "methods that reached unthinkable extremes in the violation of human rights" denote the gravity of the situation, but do not bring the reader closer to the texture of the human experience, whence he or she might be able to empathize with the victims of violence and understand the magnitude of the damage caused. Regarded from this perspective, the notion that those disenfranchised from their home and land, and forced to displace themselves to other places "start a new life", does not reflect clearly or forcefully enough the drama of the irreparable losses, estrangement and trauma, nor the challenges and courage of those who manage to begin anew or return. By not distinguishing the experiences of diverse population groups, the many hues and diverse ways in which violence against the civilian population constitutes a weapon of war are lost. For example, the textbooks do not include references to the terror, humiliation or intimidation generated in communities by the invasion of armed groups, the frustration caused by physical wounds, the life projects truncated by illegal recruitment or trauma caused by sexual violence, among others.

Portrayal of victims in ¡Basta Ya!

In contrast with the school textbooks, ¡Basta Ya! situates the memory of violence victims at the center of the narrative. This accentuates the conflict's human dimension, while their perspectives question the different armed actors who were responsible for the violation of human rights, whether these groups are rightist, leftist or belong to State forces.

The conflict's history is narrated in the voice of men and women who endured the deliberate violence perpetrated by different actors in confrontation. Their testimonies evidence the emotional imprint, moral damage and socio-cultural devastation generated by the war, highlighting the complexity and diversity of the victimization experiences, which go far beyond the material and economic losses.

As a Wayuu community, we were morally and culturally destroyed. The history of the Wayuu and Guajiro people changed, since they lowered their heads when the paramilitaries entered. There is neither vengeance nor war. The paramilitaries came with a clear thought: analysis of terror. To the men, several shots. To the women, cut breasts, beheaded [...]. Humiliation of men and women. With everything they did to us, they wounded us so much, that they knew how to wound us as a community and as persons, with everything we hold as sacred (GMH, 2013, p. 270).

The victims' testimonies illustrate the different modalities of violence each of the conflict's actors has employed against the civilian population. These descriptions allow for an understanding of such a repertoire of violence (the instrumental reasons), differentiated by armed actors. However, they also show how different Colombian population groups lived through these experiences and the meaning these bear in their lives.

I left with my seven children, and I carried another in the belly... They killed my husband right in front of us. So I left without my husband, without land, without clothes, without money... without anything! Alone, with so many children. I got to Montería, trying to find a way to support these children; I could not let them starve. There was no time for grief, no time for nothing. I had to find a place to sleep, a way to get the children a piece of bread and a cup of aguadepanela (GMH, 2013, p. 306).

I live dying-a 50-year old peasant told us, who lost a leg and almost all his eyesight when he stepped on a land mine 4 years back-. Now I live off alms, and whatever my children can feed me. I live with the three youngest ones... I have been like this for three years, and I am not dead (GMH, 2013, p. 95).

Finally, ¡Basta Ya! also underscores the unequal impact of violence, which affects some population groups disproportionately.

Nobody has been exempt from the war, that is true, but the reports and the data recording Human Rights violations prove how the war has not affected everyone in the same measure. The war befalls especially on impoverished populations, on Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples; it shows no mercy on dissidents and opponents, and affects women and children in particular ways (GMH, 2013, p. 25).

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we have contrasted two ways of narrating the history of the Colombian armed conflict. Data analysis reveals a stark contrast between the narratives presented by school textbooks and the ¡Basta Ya! report, regarding (i) narrative structure, (ii) explanation of the causes of violence, and (iii) representation of the victims' experience.

The fundamental conclusion is that the armed conflict narrative common to the school textbooks has serious shortcomings, which limit their contribution as educational resources in the context of a peace-building process. Our analysis strives to show how the strictly chronological structure and their "presidentially-oriented" thematic approach do not favor a critical understanding of the conflict, nor a de-legitimation of violence. In this sense, we point out how the textbooks' narrative (i) favors the State's perpective, hindering an understanding of the perspectives, goals and interests held by different actors involved in the conflict; (ii) dismembers the web of causal factors that explain the conflict's origin and transformation, thus making the understanding of its prolongation and degradation more difficult; and (c) marginalizes the victims' experience and voice, making it harder to understand the magnitude of the emotional, physical, social, cultural and economic damages endured by the civilian population. The history offered by ¡Basta Ya! displays strong points suggesting the pedagogical potential of narratives that explain conflicts in their complexity and call the readers' attention to the tragedies these conflicts generate when they are dealt with violently.

To be sure, the contrast between these narratives, from their methodological design onward, reveals an unbalance that might be disturbing. Given the Historical Memory Group's intention and perspective, it is no surprise that ¡Basta Ya! deliberately seeks to explain the war's different causes and their transformation in time, to account for the magnitude and degradation of the use of political violence, and to highlight its consequences and impact upon the civilian population. The authors' expertise and the report's length allow addressing these matters with greater detail, depth and wealth of hues; and its research-based, non-commercial character makes it possible to offer critical perspectives with greater freedom.

On the other hand, the school textbooks' structure, style, and approach do not necessarily reflect their authors' perspectives, since their production is strongly guided by official curricula, the expectation to cover a great deal of contents in a limited space, and commercial criteria that try to guarantee their success among teachers and students. The armed conflict is merely one of the various topics these textbooks have to address. These terms considerably restrict the possibilities of an in-depth and reflective treatment of crucial current problems.

Such contrast does not imply that ¡Basta Ya! has no weaknesses; and we acknowledge that the focus of our analysis does not help to make visible the report's possible limitations. Public discussion has contested, for example, the report's periodization of the armed conflict starting in 1958, because -among other things-it excludes an important number of actors and victims of political violence during the twentieth century in Colombia. A wider outlook would doubtless prove more beneficia! for the understanding attained by students. The fact that most of the research team members come from leftist-oriented historiographical approaches has also been criticized, since this is deemed to restrict inclusiveness toward other perspectives in the reconstruction of historical memory. In a broader analysis of this material and its educational uses, it could be worthwhile to consider the limitations this bias might generate when it comes to helping students understand the interpretive nature of historical knowledge, and the deeply complex challenges implied in coordinating contending narratives. Even so, we must say this contention has been frequently associated to the fact that the report questions the guerrilla and paramilitary groups' violence on a par with the excessive use of force by State organisms. From our perspective, such questioning of violence-regardless of its authors and its victims' identity-is an inevitable ethical imperative, if a critical understanding of violence is desired as a contribution to setting the foundations for a sustainable peace culture.

We cannot overlook another critique of ¡Basta Ya! as a new "official version" of the armed conflict, which excludes or marginalizes other alternative versions. Posed mainly from the left, this call into question derives from the fact that both the GMH and the CNMH were established and partially funded within the framework of the State's peace policy. Nevertheless, in light of the analysis we offer here, it is worth underscoring the report's contrast vis-á-vis what might also be considered as the "official version" of the armed conflict's history, presented by school textbooks. In this sense, the stark contrast we point at does evidence the complexity of the processes through which "official" and "alternative" narratives are configured and re-configured. Despite its limitations, this new "official narrative" shows an important potential to widen, deepen and complexify the common citizens' understanding.

Additionally, we wish to highlight how the contrast between the textbooks and ¡Basta Ya!, though particular in their specific contents, does reflect common patterns found in the narrative analysis of other historical events in the three countries included in the study framing this article. In the course of the comparative analysis, ten key narratives were identified, that define the ways historical narratives portray political violence. A recurring pattern suggests that school textbooks tend to normalize or invisibilize violence; whereas alternative materials, which address the violent past in an explicit and reflective way, tend to de-normalize violence and to foster its critical understanding (Bermúdez, 2016).

Eventually, the signature of a peace agreement in Havana may generate a favorable context for rethinking history teaching with regard to peace education. Law 1732 / 2014 established the mandatory Peace Lectures (Cátedra de la Paz) in all educational institutions, with the purpose to warrant the creation and consolidation of a peace culture. There are contested opinions on this; many think an additional class will only increase teachers' workload, without solving the fundamental problems. Others believe this ensures a specific time in the school calendar. We think the Peace Lectures may constitute a necessary space for dialogue and reflection, for instance, in light of what we have asserted in this article. Nevertheless, we see it is fundamental not only to open up new spaces, but also to transform those already existing. History teaching should offer possibilities to critically understand the present and prepare the new generations to face up to the great challenge of building a peace culture in a society so permeated by violence.

Doubtless, the challenges and possibilities of a critical approach to the Armed Conflict's history will vary greatly amongst different schools. Lizarralde (2012) exposes how violence in educational environments has been normalized in regions of the country where the armed conflict is most acute. He argues that fear conditions most interactions in schools, thus generating attitudes that normalize violence as a protective mechanism. Yet he highlights experiences in educational communities where solidarity and support networks have helped develop innovative pedagogical proposals aiming to transform the violent imaginaries of war. We think the narratives whence armed conflict history is taught may well support this transformation. Even then, more investigation is needed on teachers' experiences in teaching these topics (Ávila, 2012), and above all, in attempting to do it in a critical and reflexive way. This is part of our inquiry's second phase, in which we have explored the challenges and opportunities teachers face when they are committed to a transformative education, as in different schools in Bogota and the Magdalena Medio region.

Notas

1 It is not clear yet what would happen to other guerrilla groups and criminal bands.

2 The Colombian educational system includes eleven grades. Ninth grade is the last year in the secondary basic educational cycle, followed by two years of middle education.

3 This title translates: Enough! Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity".

4 After its publication in 2013, the National Centre for Historical Memory (CNMH) has deve-loped school textbooks and other classroom materials, which follow the same approach and narrative structure. Given that these other materials were not finished yet at the time of our analysis, we opted for analyzing the ¡Basta Ya! Report.

References